Healing Power

Malachi Edwin Vethamani

After Daniel’s father took on a new job which kept him at work, on one oil rig or another, somewhere off the coast of Sarawak, his Amma was very much a single mother to her three children. This brought their uncle, Rabin Mama, more often to their home. Every time his Amma needed an adult to take care of the children she would turn to their Mama. He somehow got used to being at her beck and call.

Rabin Nathan ran his own business and was at the peak of his career. With his MBA and the money he had inherited from his father, he set-up an international event-organising company. Initially, through various family contacts and later his own networking, he had a steady flow of new and returning corporate customers. Despite his nonchalant appearance, he was an astute businessman and over the years had built a strong customer base. With a pool of reliable staff to manage the day-to-day running of the company, he now had time to pursue his other interests, playing golf and travelling. And between these things he also got used to his elder sister’s “Rabin, I need your help” calls. These calls weren’t frequent but over the last few years he had worked out a system of responding to her. She only called when she needed his help. Otherwise, it would be text messages. When he saw her in-coming call he would wait for it to stop and then ask her to text him. When he read the text, he would respond as he thought fit.

Theirs was not exactly a close sibling relationship. As children they had seldom played together, nor shared any common interests. But she was his only sister still living in Malaysia, and he liked the idea of family. It was his nephew and nieces that he really cared for and had come to love, especially his nephew. He felt sorry that their father was often away. He never saw himself as a father-figure towards them. He loved hearing them call him Rabin Mama. An uncle was all he wanted to be for them.

— —

My Mama arrived after seeing Amma’s missed call and then answering her third SMS.

“Glad you’re finally here, Rabin,” was my mother’s greeting. “Daniel’s lying on the sofa. Please take him to Singam’s clinic. I’ve sent him an SMS. His nurses will know what to do.” We have ‘family privilege’ at Singam Mama’s clinic. The doctor in our family will have his nephew as his patient today. Amma felt we had gone past self-medication, with the medicine cabinet full of Panadol and cough syrups from Singam Mama’s clinic, and that I should now see him for his professional medical care.

Dear Rabin Mama had to deal with Amma’s urgent request to take me to see the doctor as my fever was not subsiding and my chesty cough was worsening, and it was only three days before Christmas. Amma had her Christmas-palagaram making schedule, and that took priority over anything to do with me. Appa will miss Christmas with us because of his work, but will be home for the new year. He told us that his job contracts were getting fewer and fewer, so he could not say no when one was offered. We got used to Appa being away. But I’d rather have him here. Meanwhile, Rabin Mama will do for now. We love him. Since Appa has been away, Rabin Mama comes by more often to give Amma a helping hand.

“Hi, Mama,” I heard my two younger sisters greet him from their seats. Neither taking their eyes off the iPad they were sharing. Amma was allowing them to use it to keep them occupied today, something she rarely did so early in the day. She had two aunties coming over to make muruku with her, and she needed to get the kitchen in order. Making Christmas-palagaram was full steam ahead, and I felt I was a nuisance falling ill at this time of the year.

Rabin Mama looked at me lying on the sofa, and I could tell he was feeling sorry for me. "Pity my Paati isn't here to take care of you," he said. “She would have sorted you out within a day or two. Your Singam Mama will probably put you on some antibiotics.”

I never knew our great-grandmother except from my uncle’s stories about his Paati. My own grandmother passed away before I was born. Amma rarely spoke about our grandmother, let alone her grandmother. She often referred to her as “your Mama’s Paati.”

My uncle was in another of his story-telling moods. Looking at me he started, “If Paati was alive today, you wouldn’t be seeing Singam Mama. She’d make you her kashayam, and you would be right as rain, with no more cough mixtures or antibiotics. Our Paati’s medicine rarely failed. If it did it was because your grandmother had asked for her help a bit too late.”

My uncle’s stories about his grandmother always fascinated me. She was a Wonder Woman of sorts. His Paati seemed larger than life. From his stories of my great-grandmother, she not only raised three children, she was a successful gardener, medicine woman, and even a moneylender of sorts.

Rabin Mama said his Paati had green fingers, and so her vegetables, fruit trees, and even her flower plants flourished. She was a marvel in the kitchen. Her curries and her palagaram – Indian sweetmeats and cakes were legendary; but most of all his Paati was a shrewd businesswoman. To my knowledge (and I did know quite a lot about her dealings from Rabin Mama’s stories) she was the only person the single chettiar—the moneylender— in their kampong, actually borrowed from.

Amma signalled to Mama that we should be on our way. We headed to Mama’s car. It was a brand-new BMW.

“Wah! You have a new car!” Amma used to tell us not to touch anything in his cars, as they were his most valuable possessions. “The cars are your uncle’s children. Very precious to him, don’t break anything,” she had warned.

I wasn’t feeling really unwell, so I asked him a question that would keep him going and divert him from asking about my studies, which was his main interest in me.

“Mama, so what would your Paati do for you when you weren’t well? What was this kashayam?” I asked him.

“Daniel, why this sudden interest in my Paati’s kashayam?” He smiled to himself, pleased to hear the question about his grandmother.

“Tell, lah, Mama. I’m really quite curious about it. Later you can ask about my studies,” I added, knowing that inevitable topic would certainly come up.

“It was a horrid tasting black concoction of Indian spices and herbs boiled in water. It was her speciality, and I doubt even your grandmother knew how to prepare it, the way Paati did. Despite its unpalatable taste I would gladly drink it. Paati's medicines never failed.”

— —

The visit to Singam Mama’s clinic was quicker than usual. Amma’s SMS to my uncle had worked like a charm, so we skipped the queue, and I was allowed into his consulting room as soon as we got to the clinic. As we went in, I could feel some unhappy waiting patients glare at me. It didn’t bother me much; I wanted this visit to be over fast. Family relationships have their benefits.

Later, lying on my bed, fully medicated, I waited for sleep. My thoughts returned to Mama’s Paati. How lovely to have a grandmother, I thought and dozed off quite quickly.

When I woke up, I told Amma about a weird dream I had had. I had seen my Sithi and Rabin Mama getting ready to give palagaram to their neighbours on Christmas Eve.

Amma laughed. “You’ve been listening to your Mama’s childhood stories again, and they have gone to your head. Let me check if you have a temperature,” she said, and touched my forehead. “No fever, that’s good.” She had no interest in my dream.

I went into the dining room. All the murukku-making activity was over. I must have slept longer than I thought.

“Can I have some murukku?” I asked half expecting a quick “no” from Amma. She did not disappoint me.

“Nope! Wait for Christmas Eve. They are all nicely packed and put away.”

I made a weak protest. “Your throat is not ready for murukku yet,” Amma brought the discussion to an end.

The rest of the day went by uneventfully. I was back in my room and continued reading the latest Harry Potter novel. I wasn’t too pleased that I would be on antibiotics all Christmas. One cup of kashayam would have been a welcome alternative.

— —

I had a restful night, no dreams like the one I had during my afternoon nap. Amma was busy in the kitchen, and my younger sisters were nowhere in sight. Probably still in bed, I thought to myself. My throat felt better and my cough had subsided. I was glad Uncle Singam’s medicine was doing its work.

Amma gave me quick instructions to have my breakfast and take my medicine.

“Amma, did you drink kashayam when you were ill?’

“Nope! We were given Western medicine. You look better today after a few doses of your Uncle’s medicine.”

“Amma, what’s in this kashayam?

“Daniel, why this sudden interest in kashayam?” She knew the source of my interest.

“Am sure Aunty Google will give you all the information you want. I never drank that horrid concoction. It was made only for your uncles.”

“I already checked the Internet. I found it under Ayurvedic medicine. Looks like your Paati practised her own form of Ayurvedic medicine.”

“Daniel, save this kashayam talk for your Rabin Mama. He would love to tell you more, I’m sure. I’ve got to go to Aunty Susie’s house to make chippi this afternoon. You three will go with Rabin Mama for lunch and a movie.” Then she added, “Finish your Maths and Bahasa Malaysian tuition homework before he arrives.”

I was more than willing to get the work done and have the afternoon with my uncle. My sisters enjoyed his company too, but they enjoyed their iPad more.

Before Rabin Mama arrived, I had completed my homework and was downstairs waiting for him. As expected, Mary and Naomi were watching something on their shared iPad.

“You two need a break from your iPad,” I said, all big-brotherly.

“Just a few more minutes, Annan,” said Naomi.

Mary quickly added, “Once Mama comes we’ll stop.”

Rabin Mama arrived as expected, right on the dot of twelve noon, and sounded his horn. Amma waved us off, and the girls got in the back. I, as the eldest, got to sit next to our uncle. He told us where we were going for lunch. My sisters were pleased that Mama had already booked a movie they wanted to see. We were going to a Christmas movie.

When we arrived at Dewi’s Restaurant for afternoon tea, I got to chat with Mama again. The girls pulled out their iPad the minute they heard me ask Mama about something from his childhood.

“Mama, did your Paati give you oil baths? I have been reading about Ayurvedic medicine and I found that quite interesting.”

— —

Daniel’s school year began again after the Christmas holidays and he started to prepare for his first secondary school public examination. The year passed quickly, and with the tuition classes his mother had arranged, he got the good grades needed to enter the science stream. His mother harboured secret ambitions for him to become a medical doctor and join his uncle’s private practice. She did not foresee any difficulties with her brother, as he had no sons, and his three daughters were being prepared for other professions.

“Singam Mama asked about your studies, Daniel. I told him you are doing well in the science stream. I told him you will go on to do your science matriculation in a private college. Your grades have to be good enough to enter one of the private universities. Your Appa has saved up enough for your education. You just have to do your part.”

As the months passed, this conversation was repeated. Daniel accepted it. It did not seem such a bad thing. He had some interest in medical studies. He wanted to learn the science of healing. What he didn’t tell his mother was that he had been reading about alternative medicines. He was captivated about learning from nature and its healing powers. Listening to Rabin Mama’s Paati stories, he had begun to read about Ayuverdic medicine. He discovered that that there was even a Bachelor of Ayuverdic Medicine, a pathway to becoming an Ayuverdic doctor. Rabin Mama’s Patti seemed a mixture of a medicine woman and a bit of a witch doctor now. Daniel wanted to learn about herbal remedies and medical oils which could be used to treat the sick.

He was drawn to what he read on the Internet about Ayurveda. He was yet to see an actual Ayuverdic clinic in his hometown. He Googled and discovered there were a few in Kuala Lumpur and towns where there were high Indian populations, like Klang and Ipoh. He had never been to an Ayuverdic clinic, and he hoped he might be able to go to one, with Rabin Mama, and meet an Ayuverdic doctor. He knew the only person who would entertain such an idea was Rabin Mama.

— —

One Sunday afternoon, Rabin Mama joined us for Amma’s puli soru, prawn sambal and lamb tripe curry lunch. He never could say no when she invited him with her speciality menu. He even cancelled his Sunday round of golf with Uncle Samuel for her puli soru. Behind her back, he’d tell us that no one could beat his Paati’s puli soru. His Paati’s ingredients of tamarind and all the spices would have been measured in her own fashion. Once cooked, it would all be tied into a bundle with a white muslin cloth and kept overnight. Neither their Amma nor mine could match his Paati’s puli soru, he repeated. He added loudly for Amma’s benefit, “Your Amma’s cooking is still any time better than the restaurant’s, any time.”

“I heard your whispering to the children. You don’t have to compare my cooking with your Paati’s cooking. Don’t spoil my lunch with ‘Paati’ this and ‘Paati’ that.” Amma’s voice sounded irritated but she changed her tone and invited us to start eating. As usual, she served my uncle first and then went on to help us to our food.

After lunch Amma and the girls went upstairs to watch an Indian movie on Astro, and I had some time to chat with Rabin Mama.

“Mama, tell me more about your Paati’s medicine. You mentioned mantaram once and asked me to remind you about it.”

He laughed in his gentle manner and said, “Besides kashayam, Paati used to do a treatment of her own making. Something she probably learned from her own mother. As the kashayam simmered in a blackened clay pot over a woodfire stove, she worked on a second “treatment”. Paati knew every ingredient and its proportions. I watched her prepare her healing medicine many times but could never make out what she put into a piece of cloth.

“Each time, Paati would tear a piece of cloth and swiftly move through the kitchen taking a little bit of this, and a little bit of that, from her different Horlicks bottles in the kitchen. Then she'd tear a little bit of attap from our roof and add a pinch of sand from our front yard into her cloth. She'd then roll it into a small round ball, about the size of a ping pong ball.

“Now she was ready to use the cloth-ball on me. I knew just to stand still, and not say a word. Paati would gently rub the cloth-ball, starting with my forehead. She would then move it over my eyes and down to the shoulders. Paati rubbed the ball all the way down to my toes, covering just about every part of me.

“Once she had reached my toes, she would ask me to spit on to the cloth-ball. Then she'd take the ball to an open woodfire stove in the backyard, that had wood smouldering in it. Just as she was about to throw the ball into the fire, she too would spit on it and throw it into the glowing fire. That would take care of the evil-eye that caused my illness, she once told me.”

Daniel listened to his uncle, fascinated with what was being described to him. He yearned for that world, which had passed him by. He had come into the world a little too late, and had missed meeting this mysterious grand woman.

“Over the years, I have learned to stop mocking my Paati's rituals. I always got well, though I sometimes suspected the ritual had little to do with my eventual recovery. But Paati was so very loving in her endeavours, and I was more than willing to be subjected to her mantaram. Besides, I enjoyed every minute of her attention,” his uncle ended his reminiscing.

Daniel watched his uncle lost in his own thoughts as he went silent. His uncle seemed lost in his own world. Daniel wanted to hear more about his uncle’s grandmother.

“Tell me more about your Paati. My friends’ grandmothers seem ordinary and regular people. I never knew my own Paati, and I feel I have missed out on someone wonderful,” Daniel coaxed his uncle.

“Paati was such a strong presence in every aspect of our lives. And I always felt it more so in my life. Even today, I long for the oil baths she gave me as a child. Watching her ritual oil bath preparation, and what she did after her bath, continues to fascinate me. She would patiently rub nallennai or gingelly oil all over her body and hair. And after her bath, she would hitch a sarong under her armpits and stand outside the bathroom and dry her long hair with her towel. Despite her age, her hair had barely thinned and there was still a lot of black hair on her head. Her small body seemed strong just like one of the old neem trees in our kampong.

“I don't remember my Paati growing old. She was Paati. Ageless. We never knew her birthday. Unlike other grandmothers, she was strong and could get to the nearby grocery shops, and every Sunday she would walk to Church, which was less than ten minutes away. Her mind was strong and sharp. She read her Tamil Bible every morning, without fail. While my mother was going for eye-checks and had started wearing prescription glasses, Paati needed no such assistance. She boasted of her excellent eyesight. She told us to wash our eyes in the cold, morning water.

“Paati was born in a village in Tirunelveli and had arrived in Malaya with her parents. She married our Thatha who kept a grocery store. Unlike Paati, Thatha was not a good businessman. He was drawn to horse races and eventually lost his business. Paati was a survivor. She outlived Thatha and stayed with my Amma and Appa. She helped raise us all, and I was one of her favourite grandsons. She used to tell us stories of how she would swim in the ponds near her home. She had survived the gruelling sea voyage from Madras to Port Swettenham (now called Port Klang). I still remember our trips to the seaside resort of Port Dickson. She was the only swimmer in the family. She would try to teach me to swim but I was too scared of the water.

“I didn’t see Paati grow old. She had her daily routine. She would get me a cup of Milo before I went to bed; that was usually the last thing she did before she went to bed too.

Then one morning, Paati did not get out of her bed at her usual hour. Amma wondered where she was, went looking for her, and found Paati lying there very still. We could not believe that such a strong presence in our lives had been taken away so suddenly. There were no goodbyes. Just the final kisses on her cold cheeks before the coffin was closed shut.”

— —

My interest in Ayuverdic medicine grew as I heard more stories from Rabin Mama about his Paati. My mother didn’t know what to make of my interest in Ayuverdic medicine. As long as my grades kept improving and I did well in my studies, I was left to my own devices. I did well in my O-level examinations and registered for my A-levels at a private college. My mother was pleased. For her, I was sailing in the course she had set for me: to do medical studies in India.

During my matriculation, I had begun to read up on various medical traditions. Eastern medicine intrigued me: I felt a strong but strange link to it. The more I read about Ayurveda, the more interested I was in it. Ayurveda was an old medical tradition and had evolved over centuries. My friends were busy applying to medical schools in this country and abroad. I had little desire to go in the direction they were drawn to. I wanted to know how I could go to India and do a Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery.

— —

“Now what?” Rabin thought on seeing his sister’s SMS. There hadn’t been the usual call before the SMS. That was strange, and quite unlike her.

Am furious with you. Come to the house asap.

He replied: In a meeting. Will get back to you.

He was finishing a round of golf with Samuel Chin, his regular travel companion and golf partner. He did not like being summoned this way by his sister. The SMS did not read like a family emergency, he thought to himself. “And why the hell is she furious with me?”

Rabin tried to remember the last time he might have upset his sister for her to be “furious”. He couldn’t remember a time in their adulthood when this had happened. Theirs had become quite a congenial relationship, with him playing the helpful younger brother and loving uncle. They rarely discussed anything that was important or serious enough to cause dissent or unhappiness for her to be “furious” with him. He was quite sure he had not done anything that would have set gossiping-tongues wagging and upset his sister.

“Good grief, here I am a grown man subjected to an elder sister’s sudden anger,” he thought to himself. “Why the suspense? Why not just tell me? Such drama!”

What brought this on?

No reply to his SMS.

Samuel Chin saw the irritation on Rabin’s face. He could tell that Rabin was more than irritated, bordering on anger. “You alright, Rabin?” was all he asked. Rabin nodded. They went on to finish their full round of golf.

“It’s my sister,” he told Samuel Chin.

Rabin apologised to Samuel Chin, “She seems to be suddenly upset with me, and has summoned me to her house.”

“Oh dear! Not the usual child-minding request SMS then. We’ll have drinks and dinner next week then. No problem,” he replied.

Another SMS came on his mobile phone. It was from Daniel.

Sorry, Mama. I think I have upset Amma. And she’s angry with you. Not sure why.

He replied: No worries. I’m coming over now.

How the two were connected, Rabin was unsure, but he knew he would soon find out. He was not one for scenes of family quarrels, and he saw no reason for his sister’s sudden outburst.

— —

Daniel greeted his uncle at the gate. Rabin had decided he didn’t want to park his car inside the house compound. His sister stood at the door and started off in a loud voice. Rabin remembered that voice from a distant past.

“You have poisoned my son’s head with your stories about your wonderful Paati. All that talk about her great deeds and how she made kashayam for you and Singam and used traditional medicine for your different childhood illness and ailments. I thought it was all harmless idle talk, but your stories have made Daniel go silly.”

Rabin stared unbelievingly at his ranting sister, and walked into the sitting room.

“What is this about? Why don’t you calm down and tell me what is going on in that head of yours?” Rabin said in his unruffled voice.

Daniel began to realise what had brought on his mother’s anger. They were talking about his undergraduate studies, and Daniel had mentioned to his mother that since she was planning to send him to India, he might as well do a degree in Ayuverdic medicine. His mother’s face grew dark at the very mention of Ayuverdic medicine, and she yelled at him, “You will do no such thing. What rubbish has your uncle put into your head!” At that, he watched his mother take out her mobile phone and text his uncle. She told Daniel to shut up. She was going to talk to her brother and tell him to stop meddling in her plans for her son’s future.

“Your stories about Paati and her miraculous medicine have gone to Daniel’s head. He is now talking about wanting to go to India to do a bachelor’s degree in Ayuverdic medicine. You are wrecking all my plans for him.” Daniel heard his mother shouting at his uncle.

Rabin could not believe what his sister was saying. Her resentment towards Paati after all these years had lain dormant and waited for an opportunity to burst out. He felt this outburst was all about Paati. His sister had often complained to their mother that Paati had treated her unfairly. That her brothers always got preferential treatment. They were served first, got bigger shares, and at times she even had to wash the plates they left in the sink.

Rabin knew that it was quite obvious that Paati was partial to her grandsons. Paati, however, was never mean to their sister. All their sister’s grumbles to Amma had no effect on Paati. Soon she grew sullen and hung on to their Amma’s saree mundhanai, and followed her around. Now, she finally had the chance to say what she thought of Paati and him. There was no one else in the family for her to direct her anger at.

“Rabin, keep your wonderful Paati to yourself. My children do not need to hear about her. I thought I had got rid of all that Paati nonsense, but here she is coming back from the dead to claim my son!”

“Stop your nonsense about Paati,” Rabin said in a raised voice. “I know how you feel about her, but this has nothing to do with her. Just stop it now before you say something you will regret - or you will never see me set foot in your house again.”

His sister immediately went silent. She knew Rabin would keep his word on that. She also knew what he was for her. She needed him around to help her, because there was no other adult in the house, especially, a man. She blamed her husband for putting her in a position where she had to depend on her younger brother. She had tolerated his constant mentioning of their Paati whom she had barely liked. She thought the Paati stories were harmless, just a way Daniel could connect with his uncle.

Rabin sat there taking in all that his sister said. He suddenly wanted to laugh. He wanted to laugh in her face and tell her how pathetic she had become. She had kept in her anger against Paati all these years, and today she had found the opportunity to shout out her antagonism towards a woman who had died so many years ago.

He felt pity for his sister. That was now the feeling he always felt for her. It was pity that made him come to her assistance. His only comfort in being with his sister and her children was the sense of family, that he longed for and could never have. All their family members had gone their separate ways. Singam was busy with his own family and his clinic. The only other sister had settled in Australia and rarely came back to visit. And Rabin had his big empty house with his two cats to go back to every day.

The two girls were probably in their room upstairs. Daniel sat on a chair across from his favourite uncle, looking at him. He had avoided sitting next to him on the three-seater settee. His mother was standing next to Daniel. She finally sat down on a chair next to Daniel.

The silence was heavy.

Daniel’s mother suddenly called out to the maid in the kitchen and asked her to make Rabin a cup of coffee. Her voice was calmer now.

“Daniel, go to your room. I want to talk to your Mama, alone,” she said.

Daniel fled, leaving the two adults alone in the sitting room.

She needed him to speak to Daniel. If anyone could talk Daniel into changing his plans, she knew his Rabin Mama could. Rabin waited for the Bru coffee to arrive and regretted cancelling his dinner with Samuel Chin.

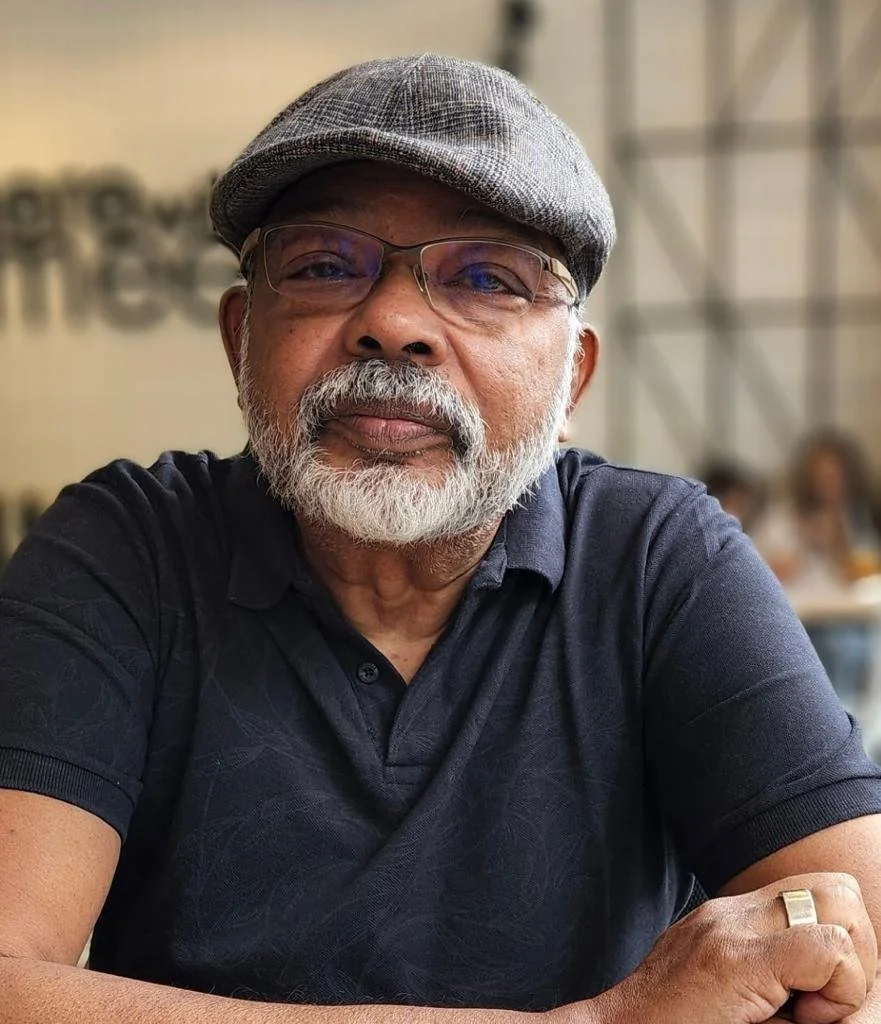

Malachi Edwin Vethamani is a poet, writer, editor, critic, bibliographer and Emeritus Professor at University of Nottingham. His publications include: Rambutan Kisses (2022), The Seven O’clock Tree (2022) and Love and Loss (2022), Coitus Interruptus and Other Stories (2018), Life Happens (2017) and Complicated Lives (2016). Three of his stories from this collection were reworked as monologues as performed as ‘Love Matters’ by Playpen Performing Arts Trust in Mumbai in 2017 and 2018. His short story ‘Best Man’s Kiss was reworked into a short play for an event called ‘Inqueerable’ organized by Queer Ink in Mumbai on 8th September 2019 to celebrate the first anniversary of the Supreme Court of India overturning Article 377 of the Indian Penal Code which had made consensual homosexual sex illegal. His individual stories have appeared in Literary Page, New Straits Times (Malaysia), Lakeview: Internal Journal of Literature and Arts (India), Business Mirror (The Philippines), Creative Flight Literary Journal, (India), Queer Southeast Asia Literary Journal (Singapore) and Borderless Journal (Singapore). He is the founding Editor of Men Matters Online Journal (December 2020).