A is for Anoora

Artworks by Anoora Chapek from the 2022 exhibition Savage Punk Abstractionism.

Text by Antares Maitreya. Photography by Antares Maitreya and Honey Khor.

In 1992 I relocated from KL to Pertak, Ulu Selangor, and lived by a wild mountain stream with the indigenous Temuan tribe as my nearest neighbours. There was a bamboo hut on the property that needed a new roof and floor and I chanced upon Anoora’s mother, Indah Merkol, and stepfather Rasid Aus, fishing in a nearby stream.

They said they could help fix the hut and that’s how I got to know the whole family, because quite a few of them got involved in collecting bertam leaves for the roof and splitting bamboo for the floor. It took about eight days to get the roof and floor replaced. We threw a party to inaugurate the Official Residence of the Ceremonial Guardian of Magick River and that’s how we got to know our Temuan neighbours better.

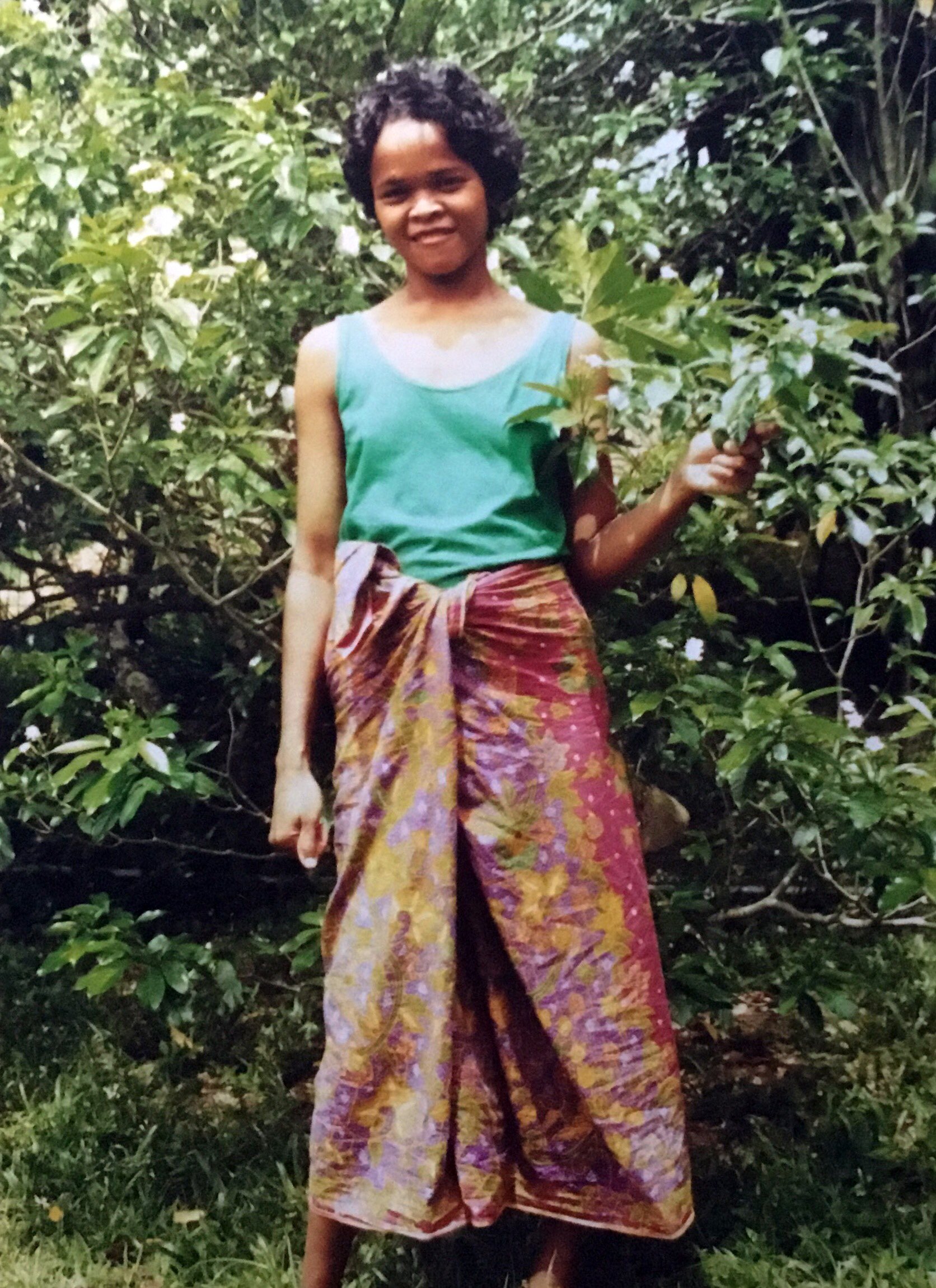

The first time I visited Indah and Rasid in their village down the road, Anoora came to the door and when she saw me she turned and ran back inside the house. But on my second visit I had my SLR camera and all the kids crowded round to be photographed. Anoora, who was called Noor by her family, stood shyly apart and when I asked if she would like to be photographed too, she smiled and nodded.

Over the next few years, I managed to gather more information about Noor Chapek. She was born 14 April 1971 at the Hospital Orang Asli Gombak and someone arbitrarily gave her the name Noorhayati binti Chapek, even though her parents were both Temuan and would have been horrified that their daughter had been issued a Muslim name. But they were illiterate, and the Orang Asli Affairs Department had adopted a policy of encouraging Orang Asli to convert to Islam.

Her birth records indicate that she had hydrocephalus (water in the head) and appeared monstrous to her mother, who tried to sell her to one of the nurses. By the time the water in her skull was drained she had suffered a degree of cerebral damage. Since Indah was indifferent to the baby, her father Chapek Jalil decided to take the baby to his sister in Pahang for fostering. Indah and Chapek were not getting along and eventually separated – but not till they had produced one last child together, a boy named Atut.

After Chapek left her for another woman, Indah burnt her children’s birth certificates in anger, so when it came time for Anoora to get an identity card, the Orang Asli Affairs Department arbitrarily assigned her a random birthdate (4 June 1978), making her seven years younger than her true age. Her name was also shortened to Noor binti Chapek. She had contracted poliomyelitis when she was a toddler, just like her oldest brother Kasim, and they both ended up with a pronounced limp.

Intergenerational Pattern of Trauma

Indah Merkol had lost her parents at age 10, when her tribe was rounded up by British soldiers and forced to live in an Orang Asli encampment with a barbwire fence and sentries on 24-hour watch. The British Military Administration wanted the Orang Asli out of the jungle, so they could not supply Chin Peng’s guerrilla army with food. Hundreds of Orang Asli became depressed and succumbed to all manner of fatal diseases, and this is how Indah lost her parents. This is why Indah’s children never had much mothering and grew apart from her when they had their own families.

When I got engaged to Anoora, I asked her if she would mind my adding two extra A’s to her registered name, so that it would sound more melodious. The way her family pronounced the Arabic name “Noor” they made it sound more like “Noh.” Anoora seemed to like her extra A’s, but her family started calling her “Norah” (unable to hear the difference the additional A’s made to her name).

I learned that Anoora had flunked Primary One twice and after that she stopped attending school. Perhaps she was unable to put up with being bullied by other kids or being pressured by well-meaning but heavy-handed teachers. Anoora’s father Chapek decided to retrieve her from his sister’s home in Pahang and bring her back to live in Kuala Kubu Bharu, in Kampung Tun Abdul Razak, with his new wife Uman and her own children from a previous marriage. I don’t know what age she was when she was relocated to KKB. Probably when she had polio, but that’s just a guess. I visited Chapek and Uman in Kampung Tun Abdul Razak from time to time after he had a stroke and was no longer able to tend his huge durian plantation in Sungai Tua, near Batu Caves.

Chapek Jalil, I learned, was descended from a bloodline that had been assigned the guardianship of Batu Caves – originally a Temuan sacred site associated with the legend of Nakhoda Si-Tanggang (which has in recent decades been co-opted as a Malay folktale). As it turns out, a similar legend exists among many other indigenous tribes around Southeast Asia, warning against the arrogance that comes with elevated social status, causing us to despise our own humble origins.

On her mother’s side, I learned that the family totem was the dragon (naga). Anoora’s famous aunt, the celebrated Temuan ceremonial singer Minah Angong, often claimed that she could summon the dragon by singing a certain song to the river. Anoora’s late uncle Utat Merkol (who was married to two elf-maidens, called Orang Halus by the Temuan) once told me that I was married to the last of the tribal Dragonkeepers. Another uncle, Diap Ketum or Seri Pagi, was the last storyteller of the Temuan of Pertak.

When I met Indah and her third husband Rasid in 1992, Anoora had only recently moved in with her mother after living for years with her father in Kampung Tun Abdul Razak. This was decided after they realised she was susceptible to being lured into the bushes by smooth-talking young men during all-night wedding parties. Little did they know she would end up living with someone from an entirely different world.

Many have wondered (but never dared ask me) why I decided to marry Anoora Chapek. Her own mother believed that her daughter had been possessed by an elf-maiden who fell in love with me when I first arrived in this enchanted area. For my part, I only know that my heart spontaneously expanded when I met Anoora and learned about her difficult entry into the world and the travails of her childhood. I felt compelled to ensure that her later years would be pleasant and joyful beyond all expectations.

Anoora, 1992. Photo by Antares Maitreya.

Anoora and baby Ahau, 1996. Photo by Antares Maitreya.

Anoora, 1998. Photo by Willard Van De Bogart.

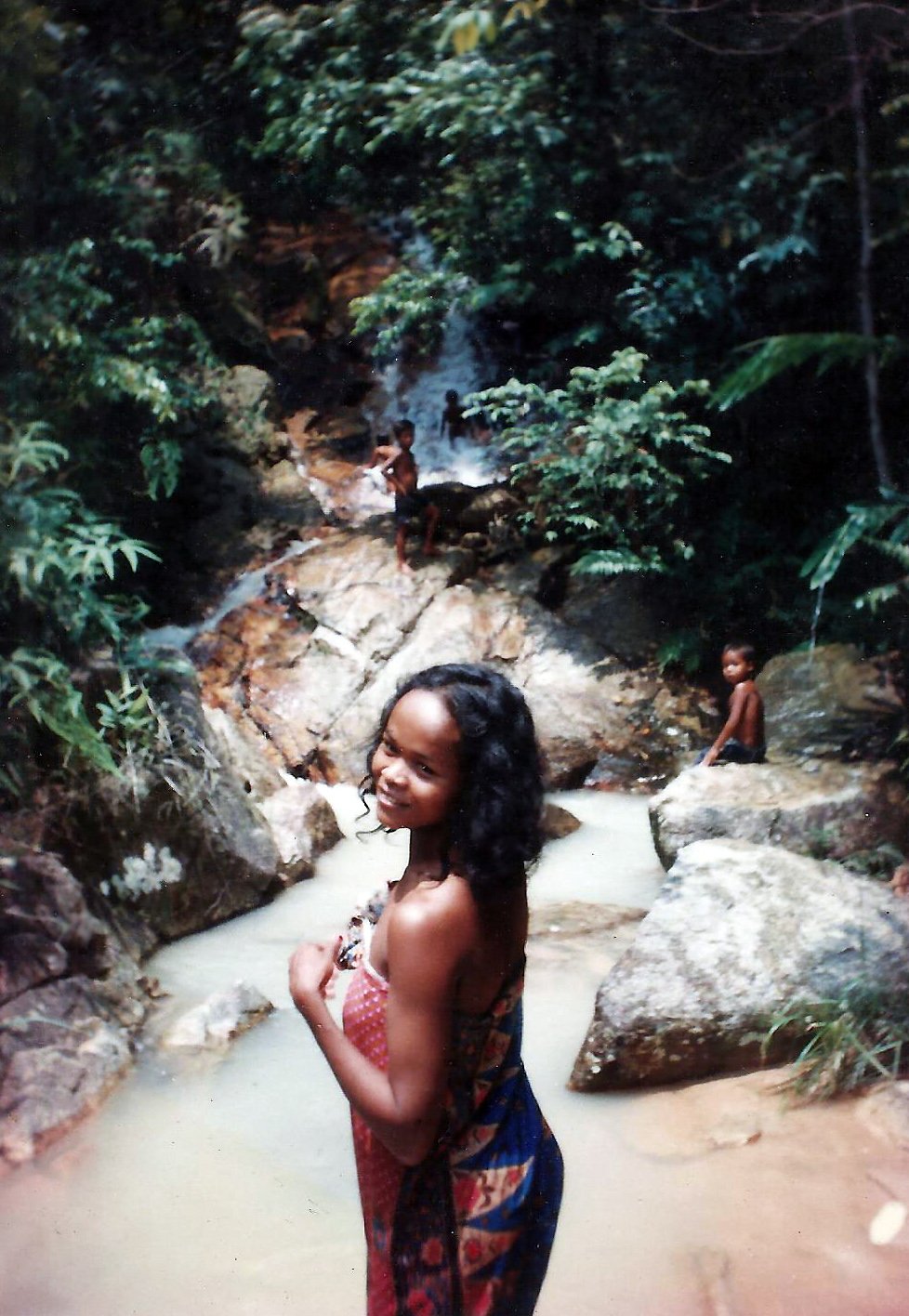

Anoora at Lata Puntung. Photo by Antares Maitreya.

Anoora at Work, 2022. Photo by Honey Khor.

Anoora, "Siapa Picasso" 2022. Photo by Honey Khor.

'Ahau' – Acrylic on Canvas. 35cm × 50cm. 24 Aug 2022.

'Anak dan Ibu' – Acrylic on Canvas. 75cm × 60cm. 8 Oct 2022.

'Nama Saya Anoora' – Acrylic on Canvas. 40cm × 50cm. 12 April 2022.

'Cintamani' – Acrylic on Canvas. 92cm × 92cm. 5 April 2023.

'Ikan Kelah' – Acrylic on Canvas. 50cm × 70cm. 25 Oct 2022.

'Merdeka 2021' – Acrylic on Canvas. 50cm × 60cm. 31 Aug 2021.

'Mungkin Boleh' – Acrylic on Canvas. 50cm × 60cm. 28 April 2021.

'Nasi Campur' – Acrylic on Canvas. 50cm × 70cm. 9 Dec 2022.

'Pokok Keluarga' – Acrylic on Canvas. 92cm × 92cm. 9 Dec 2022.

'Rajabomoh' – Acrylic on Canvas. 152cm × 92cm. 8 Oct 2022.

'Siapa Picasso' – Acrylic on Canvas. 152cm × 77cm. 13 Dec 2022.

Anoora Chapek (born Noorhayati binti Chapek on 14 April 1971) was renamed Noor binti Chapek and reassigned an arbitrary birthdate (4 June 1978) by the Department of Orang Asli Affairs after her mother burned her children's birth certificates in a fit of rage at her wayward husband. She struggled with severe emotional trauma until she discovered painting in early 2021, under the gentle guidance of art therapist Honey Khor.