How the Koitur Adivasi literature remains on the margins of Indian literature

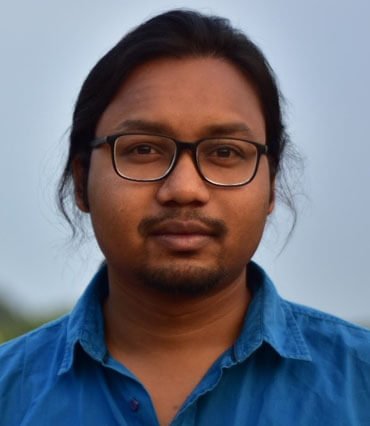

Akash Poyam

Where will I go?

Oh my dear people of my land my country

The time has come to leave, my friend,

Ah, ah for our birth land

Where can I stand, or sit…

Who will speak for us?

They are coming

With marching legs and arms!

They are crying to buy our land

Where will we go?

Oh are you taking us to paradise?

Oh my children sleep well

We will fight

We don’t know their machines

My soul is boiling

They are flooding us with money

They are coming to take our mountain

And use it all up in 25 years

Very clever, dear friend…

Oh dear frogs and fishes of my river,

Will we be able to blink at each other anymore

Will I be able to catch them?

We are tired of this struggle[i].

These words of Salu Majhi, an elderly, blind Kondh storyteller from Odisha’s Kucheipadar, pierce through us as he describes the pain of ongoing destruction of Adivasi territories and violence, and reminisces about his past relationship with nature. Majhi’s song represents a beautiful literary prose when it’s translated and put down in written words, until then it remains in the language and memories of him and his people. Such is also the reality of the large majority number of Adivasi communities, who carry rich and diverse literature in their memories and their languages. But due to the absence of written literature, are considered as people without history, literature, and knowledge.

In India, where various states were created after independence based on the ‘linguistic’ criteria, languages carry power and produce hierarchies among the people and therefore also define the fate of these societies. Among the 22 officially recognised languages in the Indian constitution in the Eight Schedule, there are only two Adivasi languages that were only added to the list in 2004. The ministry of human resource and development in 2014 identified 42 endangered languages, with less than 10,000 speakers. Almost all of these languages were of tribal communities. As a result of marginalisation and negligence of Adivasi languages since independence, the Adivasi communities have found it difficult to preserve in their oral literature. Among the Koitur people, for instance, at present only 30 per cent of them speak their own mother tongue, even though the first Gondi script and dictionary was already written during the early twentieth century.

On 14 September 1949, during the Constituent Assembly Debates, Jaipal Singh Munda – an Adivasi representative from erstwhile Bihar and former Olympic winner hockey player – proposed that Gondi, Oraon and Mundari should be included in the Eight Schedule. Munda argued that Mundari was spoken by 42 lakhs people, Oraon (Kurukh) was spoken by 11 lakhs people, while Gondi was spoken by 32 lakhs people and their recognition could be a way forward to extract Adivasis’ ancient history. Munda also argued that while Adivasi languages are not recognised, outsiders’ languages are imposed on them. ‘Has any Bihari tried to learn Santhali, though the Adibasis are asked to learn the other languages?’ He added, ‘Does Pandit Ravi Shankar Shukla (the first chief minister of erstwhile Madhya Pradesh) tell me that although there are 32 lakhs of Gonds in the Central Provinces he has tried to learn the Gondi language?’

In Chhotanagpur and eastern India, where Christian missionaries started working in the early nineteenth century, a small population among the Adivasi communities could attain formal education. This substantially helped Adivasi literature grow at a much earlier and faster rate. The same was, however, not the case with the Gondwana region where the level of education remained relatively dismal. Adivasi communities have preserved a vast sum of literature and Indigenous knowledge in their memories, which have survived for generations because of its repetition in their mother tongue. The transition of their literature from oral to written, however, has been an extremely significant journey for their own struggle for the existence and protection of their ancestral territories.

In Chhota Nagpur, among the first Santal writers, Dr Majhi Ramdas Tudu started writing in the nineteenth century. His poem collection Kherwar Bonsha Dhorom Puthi was the first Santali literature and was published in 1882. Following this many Santal writers published their works after the 1930s, such as Chunaku Ram Tudu, Narayan Soren Tode, Raghunath Tudu, Sharda Prasad Kisku, among others. Another Chaivat Dai is regarded as the first Santali woman writer, who published her stories in 1952. In between the 1930s and 1950s, several first generation Adivasi writers started publishing their works in Chhota Nagpur region, such as Pyara Kerketta in Kharia language, Raghunath Murmu in Santali, Lako Bodra in Ho, Baldev Munda in Mundari and Aaayta Oraon in Kurukh.

In central India, in the Gondwana region, Bhavi Singh Masram published ‘Gondi Dharm Puran’, a history of the Gondi religion, and ‘Gondi Dharm Vichaar’, a compendium of the ideas of the Gondi religion in 1921. This could be considered as the first published literature by a Koitur-Gond writer. It is, however, extremely unfortunate that the policies of the Indian state marginalised Koitur people, their language, and culture that even after 100 years, when the first book by a Koitur was published, the community only has a handful of writers. Most of them write in vernacular languages such as Hindi, Marathi, and Telugu, and since there has never been a concentrated effort by the state in promoting Gondi language or literature, their works have largely remained inaccessible for the larger population and within the literary discourse of the country. Following Bhavi Singh Masram, Dhokal Singh Sandya Markam started publishing the Durgawati magazine in 1935, to spread Gondi Punem (Koitur belief system and religion) values. Later, in 1938, Raajnengi Rangel Singh Bhalawi published two important texts, ‘Koya Bhidi Taa Gond Saga Bidaar’ and ‘Koya Punemata Saar’.

These colonial-period publications, most of whose copies are now rare and many are destroyed or lost, are far more revealing than they seem. During the same time period, various British Anthropologists such as Verrier Elwin, Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf and Indian Brahmin or upper-caste Hindu scholars, such as G S Ghruye and MN Srinivas, were writing extensively on Koitur and other Adivasi communities. These scholars largely portrayed Adivasi communities as “noble-savages”, “uncivilised”, “backward Hindus” and so on — the stereotypes that still affect Adivasi people — however, one cannot find even a single reference to the writings of these Adivasi writers of the early twentieth century or references to the first generation Adivasi writers in Chota Nagpur as well as Gondwana region.

In the post-independence period, Adivasi literature in the Gondwana region did not grow as much because of state’s policies. However, in 1956, two books in Gondi script by the publisher Gondi Lipi Prakashan. This Gondi script was developed by Munshi Mangal Mashram, a resident of Madhya Pradeh’s Balaghat. In 1977, Kusuram Hanumantrao published ‘Gondi Dharmtasarri’ and promoted it throughout Andhra Pradesh.

Two years later, in 1979, the first Adivasi literature festival in the Gondwana region was organised in Maharashtra’s Chandrapur by Adivasi writer Vinayak Tukaram. It was attended by first generation Adivasi writers of Maharashtra such as Govind Gaare, Lakshman Maane, Rao Saheh Kasabe and others, who were largely influenced by the Ambedkarite movement in the state. By this time, the first generation of educated Adivasis had started writing, expressing and mobilising themselves, especially with Nagpur as its centre, which was home to many of the pioneer writers and intellectuals of the Gondwana movement.

Around the same time, many Koitur writers and intellectuals started doing their research – Sheetal Markam, Motiravan Kangali, Sunher Singh Taram, Ushakiran Atram and KB Marskole – visited Kachargarh in Madhya Pradehs, which is also considered as the origin place of the Koitur people. A few years later, in 1984, Koitur writer and intellectual Sunher Singh Taram revolutionised Koitur literary movement with Gondwana Darshan. The Hindi magazine is the second oldest magazine published from the Gondwana region and is still running.

Taram was born in a farmer family and because of financial constraints, his parents couldn’t afford his studies. He ran away from home at an early age, worked in farms and fields, and supported his own education since the seventh standard. Taram graduated while working as a watchman with an MA, BEd, and LLB and was later selected as an Area Organiser (Officer). In early 1980, during a conference of Koitur people at Madhya Pradesh’s Balaghat, Taram was deeply moved by an elder who had questioned the first generation intellectuals about the need of ‘showing mirror to the society – hinting towards the need for development of Adivasi culture, philosophy and literature’. That summer, Taram went back home and sold his share of ox-pair kept with his brother for 1500 rupees, and wished to use it for publishing a magazine. He wrote in an unpublished work,

I planned to use this money for publishing the magazine and shared the idea with a few people. While some encouraged me and offered help, others questioned “what will you do by publishing a magazine? How will it contribute to society? Publishing magazines is not a job for a person like you!”

Taram was determined, and finally on 19 December 1985, also the death anniversary of Veer Narayan Singh – a Koitur leader who rebelled against British government and was later hanged to death – he started ‘Gondwana Saga’ in Bhopal. Its name was later changed to ‘Gondwana Darshan’, which still continues.

Taram’s partner, Usha Kiran Atram, the first Koitur woman writer and poet and now the editor of the magazine, in an article last year wrote,

This new intellectual discourse created by the magazine became part of various seminars and community gatherings. These included Sahitya Sammelan or literature conferences across Gondwana region, starting from first Sahitya Sammelan at Bhadravati (1988), Wardha (1990), Korba (1991), Bilaspur (1993), Asifabad (1994), Bhopal (1995), Bhilai (1997), Nagpur (1998), Chandagarh (2002), Dudhi (2005), Dhamtari (2006), Bidar (2008), Utnur (2009), Raipur (2010), Betul (2011), Mahasamund (2012), and New Delhi (2017). Taram was working on an autobiographical book 18 paath 32 bahini but could not finish it. After a brief illness, he passed away in November 2018. In his lifetime, Taram wrote over 400 editorial columns and 100 articles on various issues, and became one of the most pioneering Koitur intellectuals of the last four decades.

Gondwana Darshan provided platform to many emerging Koitur writers, who took their own paths. Among them was Vyanktesh Atram, who published his first Marathi book Gondi Sanskrutiche Sandarbh in 1980, and Motiravan Kangali, who published Gondi Punem Darshan – which is considered as the most instrumental work by a Koitur writer. Kangali went on to write over 25 books and hundreds of articles on Gond culture, literature, language, religion and so on.

My own journey into Adivasi literature and history began with Gondi Punem Darshan during my graduation. It changed the way I looked at my own community, language, history, culture, and belief system. And I was disappointed that such a rich historical and anthropological text was completely ignored and never cited by any non-Adivasi academician during my research. Based on Gondi song and stories, archival literature, oral histories, Dr Kangali attempts to capture the history, culture, religion, and other aspects of Koitur people and their worldview. The book lays out Koitur origin stories, history of ancestors such as Kali Kankali, Jango Raaytaar, Pahandi Paari Kupar Lingo and many others.

Kangali was also one of the most learned scholars and had earned Masters in Sociology and Linguistics. He had also received a PhD from Aligarh Muslim University with a thesis titled ‘The philosophical basis of tribal cultural values among the Gond tribe of central India’. He was named by his parents Motiram Kangali. However, in defiance of Brahminical name ‘ram’, he changed it to ‘ravan’, a figure demonised in Hindu mythologies, but is considered as a king and an ancestor of the Koitur people.

For the larger part of Indian history, the story and voices of Adivasi communities have been written about by the Brahmin and upper-caste Hindus, who dominate every institution and public sphere in the country. In the Gondwana region, which was split into multiple states based on ‘dominant regional languages’, Hindi has played an extremely destructive role in the Adivasi public discourse. The Brahminical nature of the language and the culture it embodies often appears while translating Adivasi rituals, belief system, and worldview from Indigenous languages into Hindi. In the absence of appropriate words, one is often forced to use the Hindi words that represent Brahminical culture, history and symbolisms. But more importantly, Hindi imposition in India has been driven by successive governments through policies designed for Adivasi communities. This has happened through education in the dominant language, as most government schools and Ashram residential schools built for Adivasis, are largely established with deeply colonial undertone of ‘civilising mission’.

The denial of primary education in Adivasi language, and deliberate ignorance of their history, worldview and existing Indigenous Knowledge systems, has created conditions, where Adivasi children consider speaking Adivasi languages as a demeaning thing, while Hindi and other official languages of the state are considered more acceptable. While many already established vernacular languages, such as Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, Telugu and others, have managed to make their own place – largely because the people speaking these languages were provided autonomous states and were able to radically transform their literature after independence – the fate of Adivasi languages has not been the same.

Two years ago, in an article on Gondi language, I had reflected on my own experiences in native district.

Growing up in Surguja, most of us were unaware even of the existence of the Gondi language, as it was never spoken at home. The language now only remains as residues in Surgujia, a dialect of Chhattisgarhi – an Indo-Aryan language – that also contains words from Gondi. Even speaking Surgujia was regarded as ‘dehati’ (a derogatory term signifying inferiority for Surgujia speakers), while speaking Hindi was considered civilised. This led to most Adivasis of our generation unlearning the residual language of our mother tongue and aspiring to speak Hindi.

However, it is important to note that myself and our generation of young Koitur people are among the first generation to speak Hindi and our parents and grandparents had no knowledge of Hindi, while growing up.

Australian Indigenous scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith in her book Decolonising Methodologies argues that domination of Indigenous territories also took place by changing their names and therefore transforming territories. The same is the present reality of Koitur people in Surguja. My grandmother, Jangu Bai, a Gondi name of a highly revered Gond revolutionary ancestor; her village, Markadaand, comes from Gondi word Marka for Mango; however, most people in the village and her family – who have never travelled outside district – do not know about the existence of Gondi language. This is aided by the long history of Brahminical movements in this region, which attempted to introduce Hinduism among the Adivasis. In this process, the religious groups not only changed the rituals and practices of the community, but they also introduced several Hindu and Brahminical narratives into the existing Adivasi oral literature. The references to Hindu gods and goddesses in songs of Karma, a festival celebrated by the Indigenous people in the region, is the best example of this erasure and manipulation of oral history and literature. In one of the community meetings, when one follower of Koya Punem had questioned the Brahminical references in Karma songs, the young man had quickly responded, ‘my father taught this to me and I am continuing this tradition’. However, the young man was unaware of the decades and centuries of violence of Hinduism over their oral literature. This situation among Koitur people of Surguja represents the violence of dominant, hegemonic languages over Adivasi communities, and how it can destroy communities and their culture.

On one hand, the nationalistic dominating nature of Hindi language imposition on Adivasi communities has not only destroyed their own Indigenous mother tongue and its rich history, but Hindi literature has largely been responsible for the misrepresentation, demonisation, and stereotyping of Adivasi communities. On the other hand, it is important to juxtapose that regional languages – which itself are considered in threat of Hindi imposition – have been imposed on Koitur people in Odisha, Telangana, and Maharashtra.

Tenagana’s Warangal region, for instance, is surrounded by Gondi or Koya speaking Koitur people, however, majority of the Koitur people of the last two-three generations do not know their language and only speak Telugu. A few years ago, a Koya artist from Bhadrachalam district, Bokkili Nageshwar Rao, had shared that on his first day of school he was badly beaten by the school teacher because he only knew to speak Koya and could not understand Telugu. Like Nageshwar, there are many students studying in Hyderabad, who have to first unlearn their mother tongue Gondi or Koya, in order to excel in education or get a job. Similarly, Koitur people in the region believe that the Kaktiya dynasty, Hindu kings who ruled over Warangal, had imposed ban on speaking Koya, and slowly the language completely disappeared. This is a reality of majority of Gondwana region, where an alien language has been imposed on them.

While the Koitur literary discourse has largely been dominated by Marathi and Hindi writings, in the last one decade, few Telugu writings by first generation Koitur, Koya, Gond writers have appeared. Among them, Adivasi Jeevana Vidvamsam (2016) written by Koya scholar and activist Maipati Arun Kumar, is the most comprehensive book by a Koitur writer about the history of Adivasi communities in the Telugu speaking region. It documents history of several important figures and historical events — such as Sarakka Saralamma, Madvi Tukaram, and Ramji Gond among others — which have never been written about by the Koitur writers of Marathi and Hindi language. Maipati is a PhD research scholar at Kaktiya University, he has been part of Adivasi movements since he was a teenager, and his activism and political assertion is reflected in the book, where he discusses human rights violations, displacement, attack of outside religions, and so on. Another book by the first female Koya writer Paddam Anasuya Chhappudu is a beautifully written book that is immersed in Koitur worldview. Anasuya’s short stories give us a peek into Koya culture and the threat it faces with the coming of outside religion and culture. Another Telugu book on the history and religion of the Gond people of Telangana has been written by Manik Rao Ureti, a school teacher and Gondi language expert from Adilabad district.

In Maharashtra, where Koitur literary discourse largely took shape, writers of Adivasi languages and their work were given less importance over Marathi writings. Bhujang Meshram in his article Lupt ho rahe hain hamare sambodhan – our voices are disappearing – argues that most of the Marathi magazine publishers have been non-Adivasis and has given little space to the Adivasi literature, with few exceptions. Among the magazines by Adivasi publishers, Meshram writes, Jango Raaytaad – named after Koitur revolutionary who fought against gender injustice in the community – and Adivasi Bharat were two short magazines which soon closed down. Currently, a magazine named Dhol (meaning drum) is published from Gujarat, which is run by the Adivasis and for the Adivasis.

‘A poem doesn’t only speak in her tongue, but it expresses the pain in a universal language,’ Bujhang Meshram wrote in his article ‘Why Adivasi literature?’. Meshram was referring to the struggle of Adivasi poets of Indigenous languages in Maharashtra, such as Waharu Sonwane of the Bhil people, Lakshman Topale of the Warli people, Ravi Kursange of the Pardhan people, Usha Kiran Atram of the Gond people and so on, to establish themselves. These names are largely still unknown to the Indian literary world. ‘Adivasi poems represent a romantic poetry of everyday life on the lap of the nature,’ Meshram further argues. ‘Though, it also rebels against the system and establishment, their maths, peeths, vidyapeeths’ – Brahminical institutions. Unfortunately, Meshram could publish only one book while being alive, a poem collection titled Ulgulaan in 1990. His other two books ‘Marimaayi’ and ‘Ekantika’ were posthumously published. However, his contribution to the Koitur literary world remains extremely significant.

With the beginning of twenty-first century, Koitur literary discourse has reached a new milestone with the growing numbers of online publications. These online news-media platforms, publications and YouTube channels run by mostly young Koitur students are a welcome step towards preserving Koitur history, literature and their language. Two websites dedicated to Koitur people are in Chhattisgarh itself KoyaToday and Bastariya Adivasi – besides publishing everyday events and news, these platforms publish and broadcast contents related to Koitur history, culture, as well as poetry. Similarly Koya TV, Gondwana TV, among many popular YouTube channels is documenting Gondi songs, cultural and spiritual aspects of life and are an important step to promote Indigenous worldview among the young generation.

A brief historical account of Koitur literary discourse shows us that Adivasi communities have been speaking and writing for about a century, but they are still largely represented as ‘voiceless’. This assumption comes from their internalised biases against Adivasi communities, which are again a by-product of literature produced by colonial white anthropologists, as well as Brahmin and upper-caste Hindu writers. The complete evanescence of this history of Adivasi literature in-turn only helps non-Indigenous writers, for whom Adivasi communities offer a lucrative industry to research, write, and publish. The history of Koitur literary discourse in Gondwana region therefore shows us that it has traversed through a journey where it has not only contributed to the literary world, but has also revolutionised Koitur politics and ongoing Gondwana movement for the autonomy of Koitur territory, language, and religion.

— —

[i] The song has been transcribed from the documentary Wira Pdika by Samarendra Das.

Akash Poyam is a writer and copy editor at The Caravan.