From the humble to the humongous: Recasting of sacred structures along the Konkan coast

Smita Dalvi

In this essay, I write about a type of humble, unassuming and yet inherently beautiful religious building found in the towns of the Konkan belt of India’s western coast. People see and come across them everywhere, all the time, never taking any particular notice other than them being places of daily worship. They certainly don’t find a mention in any of the volumes on religious architecture of the region. I began to take a closer interest in them two decades ago when I led a team for a heritage listing project in the towns of Panvel and Uran, which lie on the coast across the harbour of Bombay. I have been living and teaching in Panvel, a port and trading town, for the last three decades and I could sense something special about these humble structures. Through my frequent travels in the Konkan belt, I realised that there is a pattern here that is commonly observed in almost every town. It is about this pattern and its speedy disappearance in recent times that I wish to write about. Both discovering the pattern and witnessing its unravelling tells me about certain societal values, long held, which are now under threat.

The narrow Konkan belt running north to south between Dahanu and Goa lies between the Arabian Sea and the Sahyadri Hills of the western ghats. Its geography, climate and culture have shaped the building practices of towns such as Panvel. Several port towns dot the Konkan belt; some of them were responsible for large-scale trading with the Roman Empire in ancient times. The port at Panvel gained prominence during the medieval period, providing a waterway for goods and people to enter inland, and join the trade routes passing through the western ghats. Passenger boats docked at Panvel up until the 1950s, after which active use declined due to the development of road and rail transportation.

For the most part, the social composition of Konkani towns such as Panvel has been like a mosaic of sub-communities. Fisherfolk, salt-makers, Hindus of various castes, Muslims of different sects, Jains, Parsis and Bene Israel Jews[i] are among the native communities. The social milieu is marked by shared cultural practices among diverse religious groups – such as food habits, dressing, surnames (last names or family names)[ii], attitudes, and most significantly, a language—Marathi—in common. This is equally manifest in the approach to building and craft practices developed over time, out of the use of local materials, and responding to the tropical monsoon climate. The townscapes consisted of modest buildings in brick, timber and laterite stone, with sloped roofs covered in clay tiles, in a low-rise domestic scale.

Compared to its size, there is a plethora of shrines and places of worship of various faiths in Panvel, all of which are community-built, or as endowments by prominent citizens. Their presence indicates a certain cosmopolitanism, but the architectural forms also point to a form of syncretism that I wish to highlight. A few of the shrines are built in an iconic style with tall shikharas for temples; and lofty domes and arches for mosques, thus conforming to the historical development of such religious architecture. However, the more ubiquitous type of shrine follows a humble, non-monumental, domestic scale. It displays a typically Konkan-style timber frame construction with sloped roofs, just like the domestic architecture.

Clockwise from top left: Owe mosque, Beth-el synagogue, Jain Derasar, Podi Maruti Temple. All from the town of Panvel or its vicinity.

Let us examine a few examples of this non-monumental religious architecture – in the above collage, can you identify the religious affiliations of the buildings by their external form alone? As can be seen from the caption, they belong to various religious denominations, yet their exteriors display a self-similar character. A masjid, a mandir, a synagogue, and a Jain derasar. They take from the building traditions of dwellings and, like them, emerge from local conditions.

These spaces are functional, built quite like the homes that the worshippers live in, and are almost indistinguishable, irrespective of religious affiliation. I have observed and documented this pattern all over the coast. This domestic scale, this visual contiguity of homes and religious places, woven together into a built fabric that made the towns of the Konkan small centres of urbanity.

The main chowk (a wide intersection of streets) in Uran where you find a string of temples, public and commercial buildings built in the local characteristic manner.

These religious buildings, some quite small, some sizeable, are truly non-iconic, having in most cases no overt symbols of faith in their exterior form and appearance. An observer would have to go inside in order to seek religious signification in the specific paraphernalia of the respective religion and its rituals. On the exterior, we may find open fronts covered with timber grills or verandas with wooden railings. Tall fenestration allows plenty of light inside — illuminating lovingly articulated interiors with carved pillars, brackets, decorative ceilings, and religious furniture – all blended together in the quiet aesthetics of timber architecture.

Over time, and with repeat viewings, I could observe subtle distinguishing marks such as the engraving of religious symbols, or the addition of subsidiary features such as a dipa-mala[iii] in a temple, or an arched gateway for a mosque. When added, these details were generally integrated into the larger aesthetic scheme of these buildings.

While the different communities in the Konkan followed their own religious practices, their physical manifestation in the public realm rarely indicated difference. I refer to this as a state of ‘unselfconscious cosmopolitanism’, which quietly echoed their other practices, such as food, dress, and social customs. The syncretism I mentioned earlier derives its formal characteristics from the material aesthetic of timber construction having its own building vocabulary. A common grammar of hipped and tiled roofs, a wooden framework of columns, beams and brackets amenable to carrying carved details, fenestration with wooden grills or wood-shuttered windows, decorative fascia boards, and so on. This grammar differs from that of classically built temples and mosques built in stone – which might have shikharas or minarets and domes respectively, giving them their distinguishing formal appearance. I was fascinated to think how these moderate shrines found in abundance in Konkan were quietly subverting accepted notions of religious architecture.

Bene Israel Synagogue and Konkani Muslim Mosque in close proximity to one another in the town of Revdanda, illustrative of ‘unselfconscious cosmopolitanism’.

Such unselfconscious cosmopolitanism in the Konkan is not premeditated, it evolved over the last three centuries and manifested itself in ways of living. Every community – be it the Brahmins, the Kolis, the Jains, the Bohras, the Parsis, the Bene Israel – used language and ritual interchangeably, and even internalised cultural signification. A charming, even poignant example of this trait is seen on a tombstone in a Bene Israel cemetery in Panvel, which has been inscribed with a verse in Marathi from a wife to her departed husband. She compares her husband with ‘Ek-vachani Ram’ (Lord Rama, who was always true to his word) and also with the purity of ‘Gangajal’ (the holy water of the Ganges). The wife, Ruby-Bai Chincholkar, seeks God’s blessing to get the same husband, Benjamin, for the next seven lifetimes. This example is not an isolated one, and similar syncretism is visible in the traditions of the other communities as well, such as the Konkani Muslims referring to their deceased elders as ‘Kailaswasi’ (residing in the heavenly abode of Shiva, that is Kailash). The Bene Israel and Konkani Muslims again share cultural affinity in their rituals and the way in which they use Marathi to describe those practices.

My wanderings in Panvel and the rest of the coast and the discovery of this pattern in folk religious architecture made me reflect deeper and wonder about the meaning it might hold. How can we possibly read these buildings? What do they tell us about communities and their culture? The observed self-similarity cutting across different religious groups, does it suggest homogenisation? Not quite. Rather, it reflects on attitudes arising out of belonging to the same geography that impacts cultural traits. These communities lived side by side, and the shrines they built coexisted in the same urban space. Spaces for reverence were spaces for functional practices, not for sub-community image-building. One can also speculate that in any given town, they were built by the same families of craftsmen. The result was a sacred architecture that revealed a material aesthetic of comfortable syncretism, binding the communities that created them.

In a multicultural region, when the attributes of identity, such as religion or caste, are mapped on those of geography and language, we get a matrix of sub-cultures. Such a theory explains the concept of culture as overlapping circles of commonality, allowing for distinctiveness as well as assimilation in a graded manner. This process, in turn, blurs boundaries between subcultures, providing specific locations for syncretism. Geography itself cannot be fixed in terms of physical boundaries – the cultural geography of one region will overlap with those of surrounding regions. It is in these locations of overlap that the melding of customs takes place; it is in this condition of blurred boundaries that we may situate the comfortable coexistence of the communities in the Konkan – so different from monocultural homogeneity.

Typically, these communities remained unchanged, even backward, for a large part of their existence. Change, as is inevitable, came to the Konkan, and when it did it was fast and irreversible. Since the time of economic liberalisation, and the schisms created by the events of the early 1990s[iv], the dismantling of the cosmopolitan ideal has been rapid. One can see a correlation between the rise in affluence and the concurrent rise in aspiration, the pan-Indian influence of dominant cultural symbols and rituals – such as those seen during festivals or weddings that overpower regional diversity – and global imperatives of homogenisation of communities on religious lines.

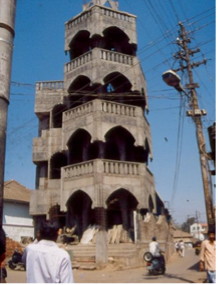

A major fallout of these trends has been the need to define and assert a distinct and non-interchangeable religious identity through material signification. There has been a wave of reconstruction of shrines in bigger and taller avatars on the same locations where they stood (and which you can see from the collage below). In this phenomenon, what is evident is a dissatisfaction with buildings that were humble and undifferentiated on the exterior, and a desire for the monumental. Over the last two decades or so, I have had the misfortune of witnessing such ‘then’ and ‘now’ shifts unfolding at an increasingly alarming rate. This is happening all over the coast where the humble is being replaced with the humongous.

‘Then’ and ‘Now’ – reconstructions of domestic-scaled shrines.

Virupaksha Mandir and Bazar Peth Mosque at Panvel.

Competitive religious valorisation, fuelled by the influx of wealth and political aspiration, has made the characteristic non-monumental and self-similar shrine an endangered entity. The desire for the monumental has resulted in strange manifestations of religious architecture that have no precedent in the history of the region’s architecture. The process has led to the dismantling of pre-existing domestic-scaled buildings, and their replacement[v] by shikharas, minarets, or domes, which vaguely mimic generic Hindu, Muslim, or Jain architectural forms.

This ‘new monumental’ is achieved, inevitably, through the use of modern material technology such as reinforced cement concrete (RCC). The edifices of concrete, plaster, and paint that are thus produced have no connection with the local traditions of craft and expertise. What they express is a larger-than-life semantic, quite without aesthetic precedent, where big is big for its own sake. This vulgarisation of the original aesthetics of the religious-space mirrors the replacement of a once low-rise domestic urban scale by an emergent high-rise concrete jungle. Every time I have the occasion to visit the historical part of Panvel town, I am filled with dread at what I will discover, and which familiar structures will have been sacrificed on the altar of revision. Those that still survive give me only a momentary comfort, because I know they don’t stand a chance.

The urbane cohesiveness that once bound communities together has frayed, with social identity taking a back seat to card-carrying religious membership in full display. The irony here is that this change is emanating from the community itself. The attitude here is not self-reflexive, but mainly aspirational. The community is at ease with these changes and considers them to be a demonstrable (and desirable) scaling up of their standards of life. What has become irrevocable is the transformed image of the city. The skylines now clearly identify these new changes as religious landmarks that are visibly different from one another.

Sites of Contest and Revision

The dismantling of the older, self-similar religious structures, replaced by an aspirational hypermodernity of symbols, signals the de-cosmopolitanisation of the small towns of the Konkan. This new practice politicises the sacred by creating dominant signifiers in the skyline, underpinning the fragmentation of identities forged on difference and otherness. One can say that not only is a syncretic form of religious architecture and its associated aesthetic endangered, but also the civility and coherence of an entire cosmopolitan society.

Smita Dalvi teaches architecture and aesthetics in Navi Mumbai and Mumbai. She is a professor at MES Pillai College of Architecture, the editor of Tekton – a scholarly journal of architecture published by the Mahatma Education Society, and has a PhD in Design from IDC School of Design at IIT-Bombay.

Her areas of interest and writings are urban heritage, cultural history, and architecture as social history. She is a co-author of Panvel: Great City, Fading Heritage (2020) (in English and Marathi). She has published several essays on cultural significance of community-built religious architecture in the Konkan and the Malabar. Her other special interest is in Indo-Islamic art and architecture on which she has delivered several guest lectures in India and abroad. In 2007, she was awarded the fellowship of 'Fulbright Visiting Specialist: Direct Access to the Muslim World'.

She is an avid traveller and a keen photographer.

Notes and References

[i] The Bene Israel (Children of Israel) are the Marathi-speaking Jewish community settled in Mumbai and all along the Konkan for several centuries. Their numbers have significantly reduced due to migration to Israel. From the mid-19th century, the Bene Israelis established about a dozen synagogues all over the Konkan, from Bombay to Revdanda. Their synagogues too display a domestic-scaled non-monumental character like the other sacred spaces mentioned.

[ii] In the Konkan, we find surnames or family names based on the village or town of origin. Thus, there are surnames like Panvelkar, Penkar, Chincholkar, Parkar, Gavaskar etc., derived by attaching the prefix ‘kar’ to the respective place name. This is customary among the Hindus, Konkani Muslims, and Bene Israel alike.

[iii] A dipa-mala (meaning a string of lamps) is a free-standing pillar, wide at the bottom and tapering at the top, occasionally placed in front of Hindu temples. It has niches or protruding brackets for placing lamps.

[iv] Here, I refer to the unlawful destruction in December 1992 of a 16th century mosque in Ayodhya (believed to be the birthplace of the Hindu god, Rama) by an extremist mob, backed by a divisive and hateful political movement. This left a trail of bloody violence and breaking of bonds between communities and ordinary people.

[v] These reconstructions are termed as ‘jirnoddhar’ or ‘tamir’ which in their original sense meant repair and maintenance of old religious structures. However, a wholesale replacement of the original form now gets religious sanction by deploying this terminology and attracts donations from the devotees.