IILUSTRATION: PAPERLILY STUDIO

The Blind Side

Sabia Rasool

On visibility, memory, and resistance.

I’ve never known what it’s like to see through two eyes. I was born with only one working eye—my left—and though doctors gave it names, I never pursued the cause. It’s just how I came into this world; partially sighted, but not blind. Over time, I learned to compensate. I tilt my head without realising it. I move slightly to one side to catch a fuller view. People rarely notice the difference unless I tell them.

But in Kashmir, the land I call home, I’ve come to believe this is not just my condition. It’s everyone’s.

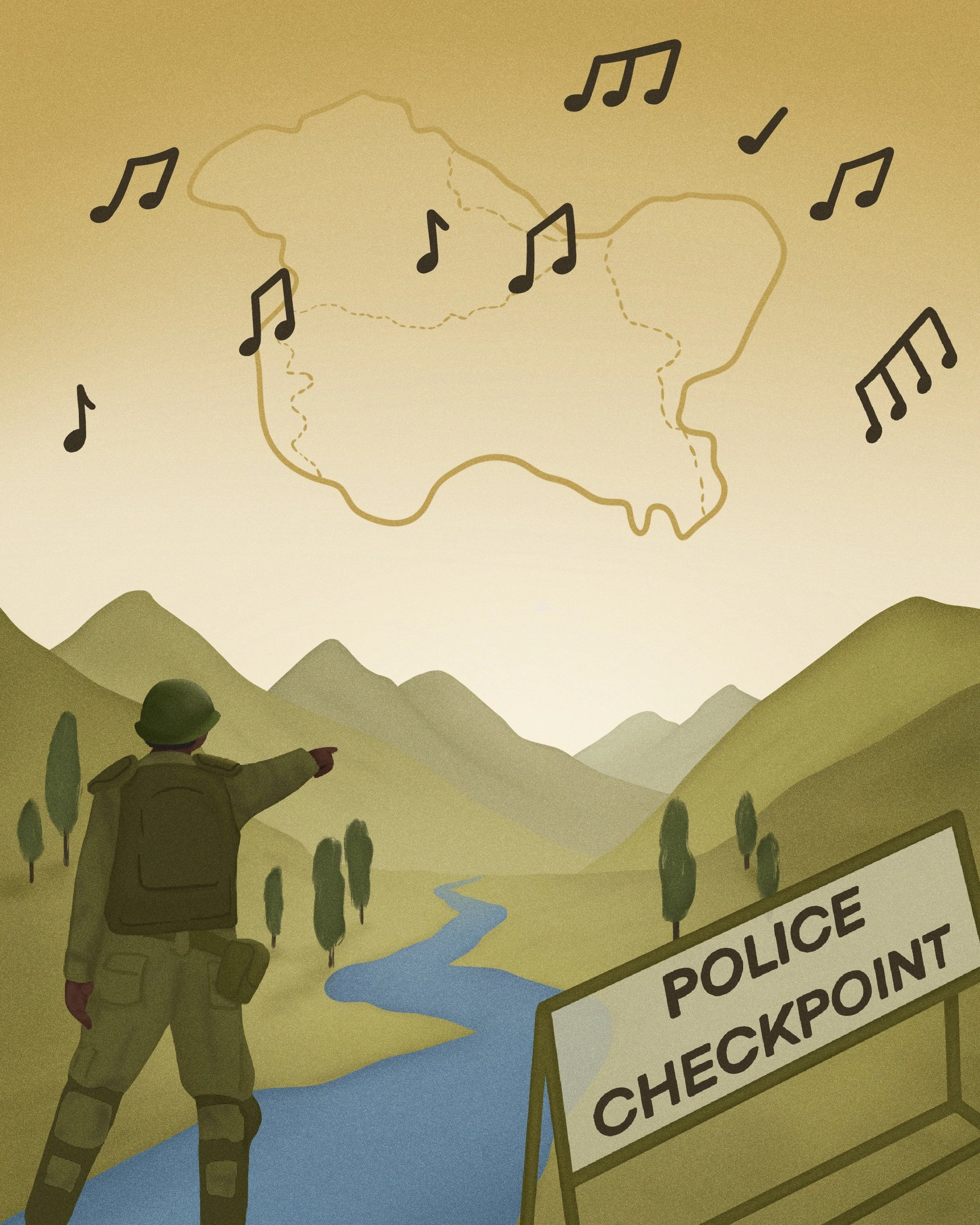

Kashmir lives on a blind side, too, a way of seeing only what is allowed and hiding the rest in shadow. People love what they see of us; snow on pine branches, saffron in tiny glass bottles, children throwing snowballs under the Chinars, mountain noses and chiselled faces. This visual vocabulary satisfies the state and appeals to tourists. The rest, including the checkpoint bruises, banned books and so much more, are on the blind side.

You have to turn your head to see it. Most people don’t.

This essay is a turn of the head.

Turning your head in Kashmir is not a simple act of sight; it’s political. The act of seeing and, more crucially, what is allowed to be seen, has been carefully curated. The visible is aestheticised while the invisible is criminalised.

And yet, what’s repressed doesn’t disappear. It mutates. It finds strange ways of surfacing; in lullabies, in wedding songs, in silences between checkpoints. It reshapes how we feel, speak, love and celebrate.

This is why Kashmir feels like a place of strange happiness. I call it “schizophrenic joy,” the half-laughter we practice when the lights are still on, and the gunshots are far away enough to pretend they’re fireworks. Here, joy is never complete. Even at our weddings, we keep one ear trained for the army jeep. In our Eid prayers, we slip in an extra line for the detained and the disappeared. Our happiness comes laced with caution and a muscle memory to run, duck and survive.

This schizophrenia is not merely emotional; it is spatial, psychological and generational.

We've constructed an entire emotional architecture around contradiction. In the same homes where wedding songs echo, we’ve hidden innocent young men in attics during raids. The same alleyways that ring with laughter on Eid have also been soaked in blood. Even as we set the table for a celebration, someone always checks how fast we can clear it.

This dual wiring begins early. As children, we're taught to enjoy ourselves cautiously. Even our toys come with caveats: don’t play too loudly, don’t wander too far, always carry your ID. I still flinch when someone taps me from behind, a reflex I can’t unlearn, even in safe spaces. I remember a cousin breaking into tears during a wedding procession when someone lit fireworks; he thought it was gunfire. Our senses no longer differentiate joy from danger. We've inherited this confusion like a birthright.

Joy never arrives unaccompanied; it’s always in the company of vigilance. And yet, it arrives despite everything. We throw weddings during curfews, we sing folk songs after funerals, and we take selfies near bunkers. Our joy is not naïve. It is resilient. It coexists with rage, mourning, and a refusal to go numb.

This is what I mean by schizophrenic joy. It is a contradiction, an ability to hold grief and delight in the same breath. Even our music learns this balance. Our songs often begin with metaphors. Our lullabies carry warnings.

I was seven when I first heard the lullaby that women in my family had sung for generations:

“Aasmaen jahaaz aav mulk-e-Kashmir,

Yimov wuch timov porr taub'e takseer.”

“When the sky ship reached the country of Kashmir,

Everyone who saw it sought God’s mercy.”

It did help me sleep, but it never lets me forget. The “sky ship” is a helicopter. A troop carrier. A memory of when the Indian military first arrived in Kashmir in 1947. It was October 27, a date still marked across the valley as “black day”, in remembrance of what never really left us. Our lullabies bear witness; they archive what our textbooks omit. A mother’s melody becomes a record of occupation, a whisper that outlives censorship.

What lullabies do at home, borders do across the mountains and lakes: they map the past onto the present. In Kashmir, memories don’t merely linger—they structure space.

Think of borders that are meant to be lines on the map. Except in Kashmir, where they become a psychological topography. More than dividing two countries, the border organises our sense of time (pre-1947, post-1989, post-2019). It mediates memory between the lived, denied, and revised, and governs our speech between what’s spoken and what’s silenced. It creates a liminal third space which is neither a state nor completely outside it. This liminality has been named as a “state of exception,” a term coined by Nazi party member Carl Schmitt. The “state of exception” has been famously interrogated by Giorgio Agamben, framing it as a condition in which the state itself suspends rights and freedoms, placing life under its direct control.

Well, for us, we just call it Monday and hope that it doesn’t get worse by Tuesday.

In this liminality, vision becomes selective. One learns to navigate the day by not seeing what can get you in trouble. But some things force you to look.

Checkpoints, for instance.

I once joked that checkpoint-hopping could qualify as Kashmir’s national sport, an activity so common and involuntary that it silently choreographs how we move, how we plan our days, even how we think. The checkpoint is a microcosm of our condition; you move forward only when permitted, and even then, with your hands raised, figuratively, and sometimes literally. It’s a choreography of submission—one we’ve memorised down to the last posture.

What makes it more unsettling is how arbitrary it all is. A checkpoint can appear anywhere; today at the nearest bridge, tomorrow on the way to the bakery. The geography of our freedom shifts without notice. It’s not just space that’s policed, but time and spontaneity, too.

That’s pretty much why I never learned to drive. In a landscape where spatial certainty is suspended by power, driving felt less like freedom and more like a simulation I refused to subscribe to.

In a place where movement is policed, music moves differently. One of the first pioneering rappers of the valley, MC Kash, gave us the anthem I Protest back in 2010. His song about civilian killings didn’t go viral in the algorithmic sense. Instead, it traveled hand-to-hand via Bluetooth and CDs, since the internet was often shut down.

That year, when Kashmir erupted in civilian protests, the state responded not with rebuttal but with repression. MC Kash’s recording studio was raided by police officers who wanted to know if there was a separatist or militant backing him. Other artists of that era were likewise pressured into silence. Many, including MC Kash, ended up quitting music under police pressure, giving up their art to ensure their safety.

Sometimes you think rock bottom is the floor. In Kashmir, that’s just where the free fall begins.

Things got worse since the region’s autonomy was revoked in 2019. The entire region was plunged into a blackout. Thousands were arrested. The internet was cut off. Phones died. We were disconnected not just from the world, but from each other. Every sound felt amplified. Every gathering felt like a risk. Even the Kashmir Press Club was forcibly shut, leaving local reporters without any independent forum. Kashmir endured 213 days without the internet, the longest ever shutdown in a democracy.

Kashmiris thought the silence of 2019 was temporary. Turns out, New Delhi liked the sound of it so much that even when connectivity returned, expression remained mute.

I was part of the growing music scene then, managing one of Kashmir’s hip-hop duos and watching as artists began to speak: softly at first, then louder, and then, not at all.

In 2021, a Kashmiri rapper named Ahmer released a song titled ID. He documented our daily humiliation of living under military occupation, especially the hostile identity verifications we’re forced to endure on a daily basis. This directness, unsurprisingly, drew the ire of the authorities. As the music video gained traction online, Ahmer was asked to take it down. You can still find the audio on the internet, but the video has vanished.

That’s exactly how it happens here. They just call to offer a “suggestion,” and suddenly your song vanishes, your event is postponed, and your courage takes a sick day.

Kirsten Han, in her essay on Singapore’s war on drugs, wrote of “treating the calluses on our hearts,” a warning against becoming numb to injustice. I often think of that line. Here in Kashmir, I fear we are developing our own calluses in order to cope. I fear the calluses on our hearts might spread to cover our eyes completely. What if we become so good at ignoring the injustice that we cease to fight it?

One way I’ve tried to reclaim feeling without losing hope is through music, specifically hip-hop. In its rawness, its refusal to lie, hip-hop became our language of dissent.

A few years ago in 2021, some friends and I began organising Cyphernama; a series of underground rap cyphers in and around Srinagar, the summer capital of J&K. Organising these sessions was not easy. The location of each session was disclosed only at the last minute, passed quietly through direct messages. Phones stayed on airplane mode. We weren’t an insurgent cell—unless rhyme counts as a threat—but we acted with the same caution. As I told a Kashmiri media outlet at the time: “We were hesitant to reveal the venue, scared to even inform people over texts because of the sensitive political situation.”

In those rooms, truth had a pulse.

I remember the first time an 18-year-old girl in one of our gatherings took the mic. She rapped in Kashmiri about growing up in a conflict zone. Her voice was neither angry nor timid, just devastatingly clear when she said: “Talking about human rights brings trouble. And being a girl makes it even more difficult.” Then she smiled. It was the kind of smile you learn to perfect when saying the truth always comes with a risk assessment.

Other voices followed.

Quoting a rapper who goes by the stage name K2:

“Curfew in my city, scariness everywhere / Arresting lil’ kids won’t lead you anywhere / I’m sorry, but I can’t rap about peace and love when I don’t see it around me.”

Kashmir’s protest music scene has been quiet for some years now. It wasn’t silenced outright, just tamed. The loudest voices either left the region or receded into the shadows of silence. The rest switched to safer beats of women, wheels, and the will to make it big; themes that don’t invite phone calls or midnight knocks.

However, the state’s appetite for control, once awakened, behaves like any predator; it doesn’t stop at the first kill. It only grows sharper, like a beast that’s just had its first taste of blood.

Once the verses were softened and the rhymes made obedient, the state turned its attention to the written word. After all, what’s a regime worth if it can’t boast equal-opportunity censorship?

I still remember the small bookshop opposite my high school in Lal Chowk, the heart of Srinagar. Bestseller, a 45-year-old bookstore, was situated in a cramped market, packed wall-to-wall with leaning shelves and a shopkeeper who always looked like he’d read too much. Back in school, we’d walk in without money, browse titles we couldn’t pronounce, then leave quietly, as if we’d carried something tangible home anyway.

Years later, I returned to find its shutters down.

The news headlines came in neat obituaries: “Just couldn’t compete with e-commerce,” “People don’t read anymore,” “The lost art of reading,” “Srinagar’s iconic Bestseller shuts down.”

It was a neat cover-up; palatable and completely untrue. But this wasn’t about e-commerce or attention spans. It was about fear and silence. About the refusal to turn one’s head and ask: what made a bookstore feel unsafe in the first place?

Days before the bookshop closed, policemen in plain clothes had raided bookstores across Srinagar and beyond, seized hundreds of books they deemed subversive. In total, more than 668 titles were confiscated in these raids. The targeted works included writings by Dr. Abul Ala Maududi, a 20th century Islamic scholar and political thinker whose works once shaped religious discourse across South Asia. His books, though legally published, were apparently too dangerous to be left on a shelf. His Jamaat-e-Islami movement is banned in Kashmir and, by association, his ideas are now treated as contraband. The police justified the seizures by claiming they were curbing “unlawful content that could disturb public order.”

In practice, they swept up everything from religious philosophy to basic texts on Islamic principles. The result is not only censorship, but a climate of anticipatory obedience. Under the shadow of Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) cases, most don’t wait to be silenced. They silence themselves, pre-empting the surprise raids, exit bans, and that familiar knock at the wrong hour.

Even Orwell might blush at the state’s creativity. The Crime Investigation Department (CID) now runs a unit called the Ecosystem of Narrative Terrorism (ENT), a term so absurd it sounds like a dystopian parody, except it’s real. In this brave lexicon, writing a dissenting op-ed, teaching the “wrong” history, or quoting the “wrong” poet can land you on a list. Academics are profiled, lawyers monitored, and journalists criminalised—not for weapons, but for words.

But here’s the thing about visibility; even when the bookstore is shut or the mic silenced, someone is still watching. Bearing witness becomes its own act of rebellion. And in Kashmir, that act can be devastatingly costly.

Nowhere is this more painfully clear than in one of the most searing stories I carry. A 14-year-old girl named Insha was looking out of her window during the 2016 uprising when the Indian army started firing pellets. The spray of iron pellets shattered the glass and pierced her eyes. Within seconds, both her eyes were ruptured, and the world went dark. Insha was not protesting. She was only watching.

Her story is too painful to recount, too political to forget, and yet, still not known enough. She became a symbol, involuntarily, of what this place does to those who dare to witness. I think of her often, not just because I was born with one eye, but because she was punished for using both.

Her story didn’t end in that moment of violence. Insha survived. She recently navigated her 12th standard exams through Braille and an unyielding will. She wants to be defined by her aspirations now, not her injuries. If she can find that courage, then maybe the rest of us can find the courage to keep looking, even when what we see hurts.

I write this as an essay, not a manifesto. It is a memory vault. A confession. A turning of the head.

It contains verses that were never meant to be sung aloud, books that vanished before they could be underlined, artists who disappeared into silence, and joy that had to be smuggled under curfews. Even I, with my one working eye, have looked away more times than I can admit. Because in Kashmir, feeling too much can break you open.

But today, I turn my head. Intentionally. Completely.

I see the checkpoints for what they are: not safety measures, but chokeholds. I see the silence around disappearances not as forgetfulness, but as rehearsed complicity. I see our fractured joy for what it is: not denial, but survival.

I was born with one eye. That wasn’t a choice. But the world’s blindness—moral, political or historical—is. It is cultivated by intention, sustained by power and excused by convenience. Thus, this blindness must be named, resisted and unlearned.

Perhaps the real threat we pose is not our protests or slogans, but our refusal to go completely blind.

So, I write this essay as both a plea and a promise.

A plea to those reading: resist the comfort of state-sanctioned peace, question the anaesthetic of narrative control and reject the silence that power so often demands.

And a promise that we will keep singing, even if under our breath. That we will pass our stories hand-to-hand like contraband hope. That we will keep laughing oddly in the face of silence. Because even fractured joy is an act of resistance. Even whispered truth can shake a wall.

What does it cost you to not know? Why place your trust in silence, when silence has always served power? And if Insha were your daughter, would you still call it “collateral damage”?

Solidarity begins with choosing to look, especially when it's easier not to. It means speaking of us in rooms we’re not allowed to enter. It means not just consuming our stories but carrying them forward. Read our banned books. Translate our songs. Don’t just share our pain—carry it into reading groups, dinner table conversations, classrooms, editorials, or even casual chats in spaces where Kashmir is only ever a postcard.

Because maybe, one day, a young girl will rap in Kashmiri on a public stage—not in defiance, but in celebration, and no one will look away.

Until then, may my words unsettle you just enough to turn your own head. May they remind both you and me that our hearts, callused as they may be, still have the capacity to see, remember and feel.

This war on memory, on feeling, on joy, cannot win.

We won’t let it.

Sabia Rasool is a writer, editor, and researcher from Kashmir. Her work explores the intersections of memory, visibility, and state violence, often through personal narrative, oral histories, and cultural critique. She is interested in how people resist erasure through music, language, and everyday joy. Sabia has worked across creative media and is currently focused on curating interdisciplinary narratives from Kashmir. She believes storytelling can be both an archive and an act of refusal.