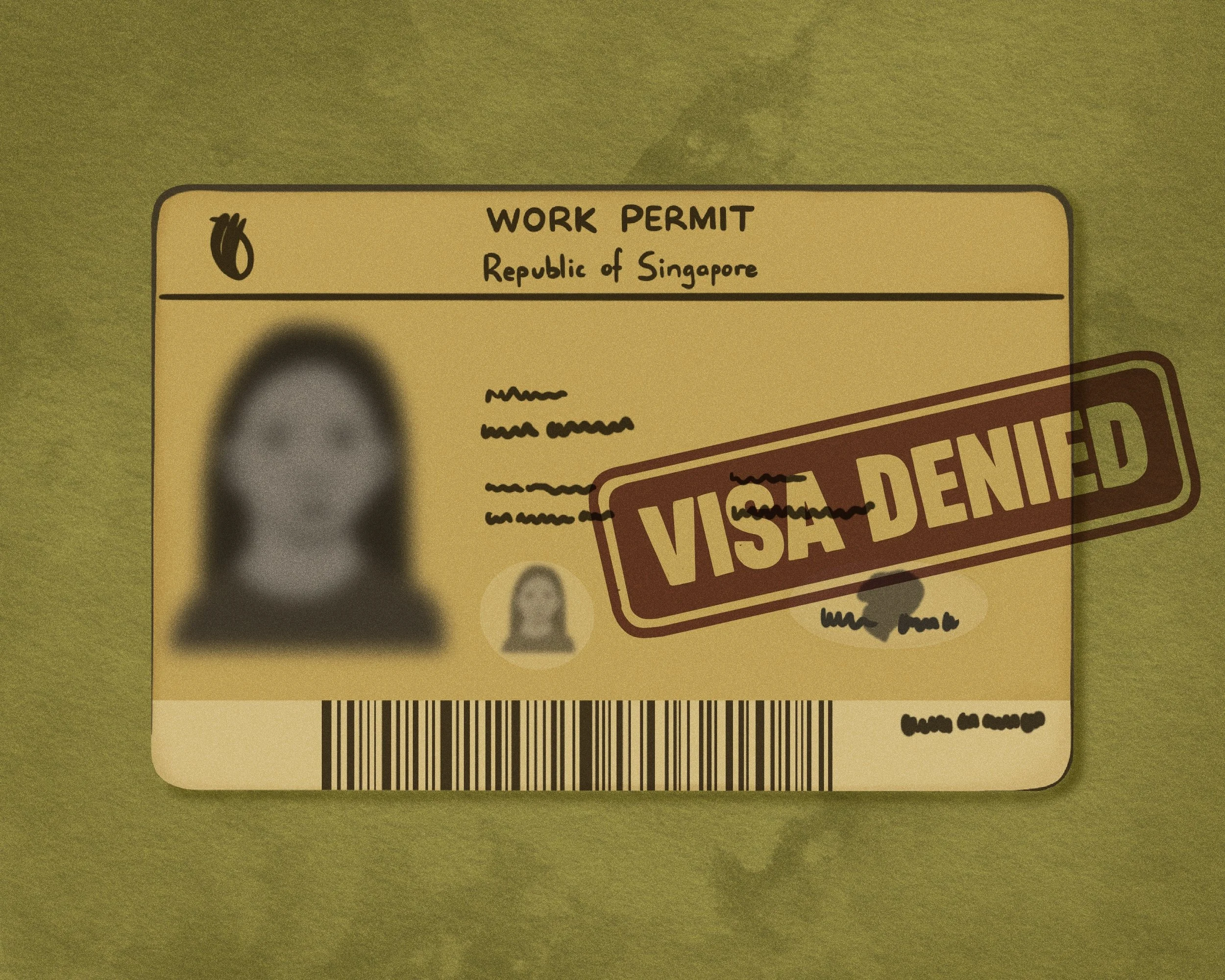

ILLUSTRATION: PAPERLILY STUDIO

Migration and the Traps of Legality

Yoga Prasetyo

Introduction

In 2021, my mum lost her job as a domestic worker in Singapore. She was legally obligated to leave the country within two weeks of her work permit revocation. And since she was too old to submit a new application, my mum had to confront what she dreaded most: going home for good. Her sudden return was both a boon and a bane. For her, leaving Singapore meant severing roots that she had sunk for 25 years, but coming home to join me was a luxury for which she had long yearned. This sense of ambivalence is palpable and all too common among Singapore’s Work Permit holders¹ who, out of financial necessity, tend to prolong their transience while simultaneously carrying the guilt of parental absence back home. Standing no chance of permanent settlement or family reunification, work permit holders like my mum are forced to stretch their families across borders and rework their parental duties transnationally, often without success. For them, in other words, family separation is an inevitable consequence of “legal” migration. Turning attention to the Singapore-Indonesia case and my mum’s experience, this essay unveils the hidden emotional and social costs of legality to think anew about the idea of safe migration.

Legal Traps

Legal or—to use a more politically correct term—regular migration is broadly defined as the authorised entry of individuals who possess valid legal documents and comply with the existing laws of the origin, transit, and destination countries. While this is certainly not a new concept, it has recently been conflated with the idea of safe migration and brought onto the global agenda particularly after 2018, when over 160 United Nations (UN) member states endorsed the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCM). Concurrent to this development, The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states have also ramped up work to promote safe migration through regional policy frameworks and campaigns, some of which are jointly run with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), International Labour Organization (ILO), and UN Women. These campaigns have now penetrated deep into some of the region's most sequestered corners, aided by not just local labour unions and civil society organisations, but also religious and Indigenous institutions. The key message is abundantly straightforward: that irregular migration is bristling with dangers, and that regular migration is the only safe path to overseas employment.

It is true that without legal documents, migrant workers would be at much greater risk of extortion, forced labour, arrest, and deportation. Yet reducing the idea of safety to a matter of legal documentation deflects our attention away from the kinds of danger that are inherent in the very legal system by which migration itself is managed. I will use the case of Singapore to illustrate this. In Singapore, those who are placed on the bottom rungs of the skill and income ladder, like my mum, are cast aside and specifically governed under the work permit system, which enforces various forms of control. For these work permit holders, migration is a “forcibly individual” undertaking as they are prohibited from either forming or reuniting with their family. Those in the domestic sector are subject to a mandatory six-monthly medical screening and will be immediately removed from the country if they test positive for HIV or pregnancy.

On top of that, it is not illegal to pay migrant workers extremely low wages since the country does not have any legal stipulations on minimum wage. Earning basic monthly wages of around S$500-800, many spend the first few years of their employment clearing their migration-related debts, which can amount to $20,000, after which they can begin saving up to fulfill their migration goals. This is one reason why the supposedly temporary migration in Singapore regularly functions as a long-term project that involves multiple periods of short-term employment. And yet, having no recourse to permanent residency, they must go home when their labour is no longer wanted, or once they reach retirement age—both of which transpired in my mum’s case.

Even when visa renewal is possible, there is no guarantee that migrants can stay on since their legal status is entirely dependent on their employers, who can legally cancel their permit at will, and, without their employer’s written permission, they cannot change jobs. At the threat of work permit cancellation with little or no safeguard against job losses, many are compelled to work incredibly long hours for low pay and contend with unfavourable working conditions, often while their passports are being withheld. At times, therefore, regular migration can paradoxically become a trap. In this case, migrants do not have any choice but to resort to self-regulation and bow to the pressures of high-handed employers—and by extension, the state—in order to secure a forever impermanent and uncertain but potentially “long-term” foothold on Singaporean soil. This legal trap is part and parcel of Singapore’s migration system whose primary function is to maintain the permanent “churning” of temporary migrant workers—providing cheap, docile, and flexible labour that is essential to the smooth running of the city-state's economy.

Diagnosing the Problem

The Singapore case casts important light on the discordance between regular and safe migrations, showing how the perils of migration are at times strongly rooted in the very legal framework many assume to offer safety. Why, then, have we associated regular or legal pathways with safe migration? I trace this issue to two separate factors that are nonetheless inextricably entangled. One relates to how migrants are placed in ranks of deservingness that are normalised and firmly established through the legal framework. Secondly, building on this hierarchy, particular categories of migrants are legally and socially positioned in such a way that strips their multidimensional subjecthood and reduces their worth to their labour and economic function. In this case, we often fail to recognise the problems with the legal framework itself because it has served its intended purpose: to designate migrant workers just as workers. I will discuss this in greater detail below.

Hierarchy of Deservingness

One fundamental problem is the normalised hierarchy of deservingness, in which those who happen to have certain skills and credentials are constructed as “expatriates” and rewarded with all sorts of entitlements, including pathways to family reunification and permanent residency, which may lead to citizenship status. Meanwhile, others like my mum are legally and socially configured as only temporary workers unworthy of particular rights. They are viewed as mere labouring bodies that are supposed to circulate back and forth—to be “used” to smoothen economic boom and “discarded” during financial downturns. These arrangements reduce migrants to their economic function and instil in us an idea that their sole purpose in Singapore is to work only, and thus their other identities—as a mother, father, social being, and political subject—must belong elsewhere, but not in Singapore. Since migrants are exclusively conceptualised as “workers,” we are then led to believe that our main concern should be how we best enforce the regulatory powers of the work permit system to uphold migrants’ labour rights. Thus, other basic human rights—such as the right to family formation and freedom from family separation (ICCPR, Art. 23)—recede from view because they hold little relevance to the economic functioning of migrant workers.

It is not difficult to see how some migrants are legally and socially positioned as chiefly economic subjects. For decades, the vast majority of policy development and civil society advocacy on migration in ASEAN—and Asia at large—have primarily revolved around labour rights. Through migration-related platforms like the ASEAN Forum on Migrant Labour, the Colombo Process, and the Abu Dhabi Dialogue, for example, member states regularly come together to discuss pressing labour issues, such as weekly rest days, ethical recruitment, the employer-pays principle, decent work, social security schemes, and workplace injury compensations—sidestepping other fundamental rights, such as the rights to family formation, family reunification, and so forth. Seeing these labour related dialogs as an opportune moment for advocacy, civil society organisations (CSOs) become inextricably bound up with such processes. While this strategic involvement is instrumental in pushing for policy reforms, it is often limiting since even in disagreement, we are required to structure our arguments within the narrow labour legal framework already defined by those in power, so much so that we have gradually lost the ability to envision other basic rights equally fundamental to human dignity.

Labour Framework: Denying Migrants’ Personhood

This, of course, is not to downplay the significance of labour rights for migrants. They are integral to migrants’ well-being, and they have far-ranging and multiscale implications. But by turning attention exclusively to labour issues, we sideline other fundamental rights and become inadvertently co-opted into the state rationale for temporary labour migration. In this regard, we are tricked into reinforcing the idea that migrant workers’ lack of other fundamental rights simply reflects their own failures to live up to particular credentials or skills that would otherwise place them in ranks to which certain entitlements are readily available. Following this logic, in other words, migrants’ limited rights and the inherent precariousness of their work are not to be viewed as “legal traps,” but simply as rational consequences of migrants’ lack of skills, earnings, and credentials. Additionally, we also are led to internalise that family separation is an unavoidable consequence of these failings, as well as a reasonable price to pay for securing the economic stability needed to keep a family together. Rarely do we ask why and how, for very specific state-made categories of workers, gluing a family together has come to require breaking it apart.

Instead of disputing the legal arrangements that strip migrants of their personhood, however, many Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) have ironically tended to grease the wheels of the system. Through migrasi aman campaigns, for example, a lot of us lock arms with Indonesian state agencies and urge our community members to use legal/regular pathways with the promise of “safe migration”. We uncritically use legality as a benchmark to assess safety, oblivious to the discriminatory provisions inherent in the legal system itself. In addition, many CSOs in Indonesia have also either created or supported “community parenting” initiatives (e.g. Tanoker, LKK PBNU, LPKP Malang) to “help” left-behind children of migrants absorb the shocks of parental migration. Yet we do not normally reflect on why this specific form of migration invariably entails family separation to begin with.

Rather than challenge the system that forces migrants to break their families across borders, most of us become compliant and play by the rules of the game. We help preserve the arrangements that enable states to profiteer from temporary labour migration while simultaneously shifting the emotional and social costs of migration to communities and migrants themselves. The guilt of parental absence can be felt in an excerpt from a letter written by my mum for the Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics in commemoration of the 2024 Mother’s Day, which reads, “Sorry you had to grow up without me. Sorry we had to live these moments separately, so much that our lives drifted apart, that you didn’t even recognise me when I came for a short visit.” Many of us feed into the system that leaves migrants feeling forever remorseful for their physical absence and for losing the irrecoverable time with their children. And when the children start showing signs of distress—withdrawing from social circles, doing poorly in school, showing rebelliousness—we come to their rescue and treat it as a kind of humanitarian issue. We help design learning modules for community parenting programs and organise games and activities to “help” them persevere through these trying times, all without sufficiently dismantling, much less challenging, the very system that inflicts harm on those left behind and those who migrate in the first place.

Rethinking our Work

The Singapore case helps us understand that the issue with “safe migration” is not only that it does not live up to its ideals, but the very notion itself is built on a legal framework that is deliberately designed from the outset to deny migrants’ multidimensional personhood. As CSOs we have lost the ability to imagine a more dignified world for migrants because we have been conditioned to internalise the hierarchy of deservingness that is normalised through a narrow labour-centred legal framework. We have lost sight of the flaws within this legal framework since, in our view, it has perfectly served its purpose: to enable and protect migrants as workers. While promoting safe migration with such rigor, it rarely comes to our attention how, despite having perfect documents or being a “legal” migrant—like my mum—we are not even close to being safe from arbitrary visa cancellation, forced repatriation, exploitation at the threat of contract termination, and sudden deportation for getting pregnant or contracting HIV.

Until we discard this framework and recognise migrants’ full personhood, it would be difficult to see what other basic rights are lacking and demand fundamental shifts in how migration is governed. Without escaping the state logic of temporary labour migration that strips migrants of their human dignity, our humanitarian-based assistance risks fuelling the system and depoliticising a problem that is both deeply moral and highly political. I am afraid we are not making migration safe by promoting regular pathways without fixing the wrongs in the very legal framework on which regular migration is predicated. Instead, we may simply be helping to funnel migrants through a system that states use to exploit them—except in fancier terms.

Footnote

¹They include those working in domestic, construction, and shipyard sectors.

Note: the term ‘migrant’ in this essay refers to ‘temporary migrant workers’ working in the domestic, construction, and/or shipyard sectors in Singapore—unless stated otherwise. I try to avoid using the term ‘migrant workers’ as much as possible, although at various points I use the term deliberately to expose and critique how migrants are reduced to their labour.

Yoga Prasetyo is currently a Research Assistant in the Asian Migration cluster of the Asia Research Institute (ARI), National University of Singapore. He draws on his unique background as the child of a migrant domestic worker and his extensive involvement in civil society movements to inform his scholarly work. He has recently completed an MA in Migration Studies at the University of Sussex. In his dissertation, Yoga used time, space, and skill as analytical lenses to examine how the Singapore state enforces multiple regimes of control on migrant construction workers (MCWs), and how MCWs interact with these structures of power to stake their claims to the city. Yoga’s dissertation won multiple awards at the university and UK levels.